a16z-Backed Shef Plays Fast And Loose Against Food Safety Regulations

October 27, 2021

Read Time

9 min

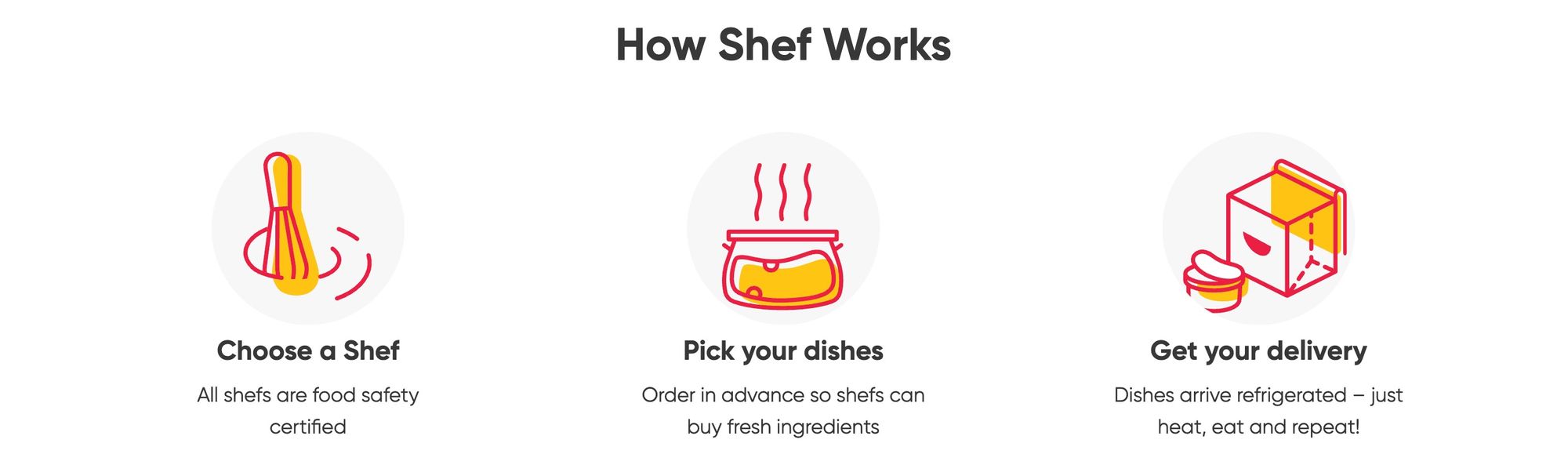

I’m no Anthony Bourdain, but I’ve been fortunate to try enough strange high and low-brow foods in my lifetime: ant-covered steak tartare, cod milt (sperm sac), grasshoppers, and street rabbit in Peru to name a few. However questionable those experiences were, never were those foods made ‘illegally,’ per se, from an unlicensed kitchen. But last night, I tried illegal hummus, labne, stuffed grape leaves, green butter chicken, and dal thanks to a new fast-growing, YCombinator-bred marketplace for local home chefs called Shef. The platform’s tagline vaguely states “enjoy local homemade meals from the comfort of your home” and says that food safety is its #1 priority. Anyone who understands the restaurant industry knows that it is against local health code to operate an unlicensed kitchen from your home for the purpose of selling meals for delivery or takeout, despite a 2019 attempt by a YouTuber to sell microwaved frozen pizza from his home on UberEats. Shef has raised $28.8mm from blue chip VCs like Craft Ventures and Andreessen Horowitz along with a host of celebrity angels like Orlando Bloom, Katy Perry, Padma Lakshmi, and chef Aarón Sánchez. But despite the legitimacy of its cap table, HNGRY uncovered questionable tactics that the startup employs to play fast and loose against state and local municipalities who have yet to adopt approved frameworks for such home chef businesses, known as “microenterprise home kitchen operations” or MEHKOs for short.

Just like Napster claimed it was never responsible for copyright violations under the DMCA safe harbors for user-generated content sites, Shef is pushing liability onto its chefs without telling them what’s at stake. While there are currently seven counties throughout California that have adopted AB-626 legislation allowing MEHKOs for home restaurants generating under $50k per year, Shef only operates in two of those counties. The majority of its operations in Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, Austin, Houston, Seattle, Boston, and Chicago are all home to hundreds of illegal operations. Over the last two years, the startup has served more than a million meals and has a waitlist of 16,000 chefs looking to join the marketplace.

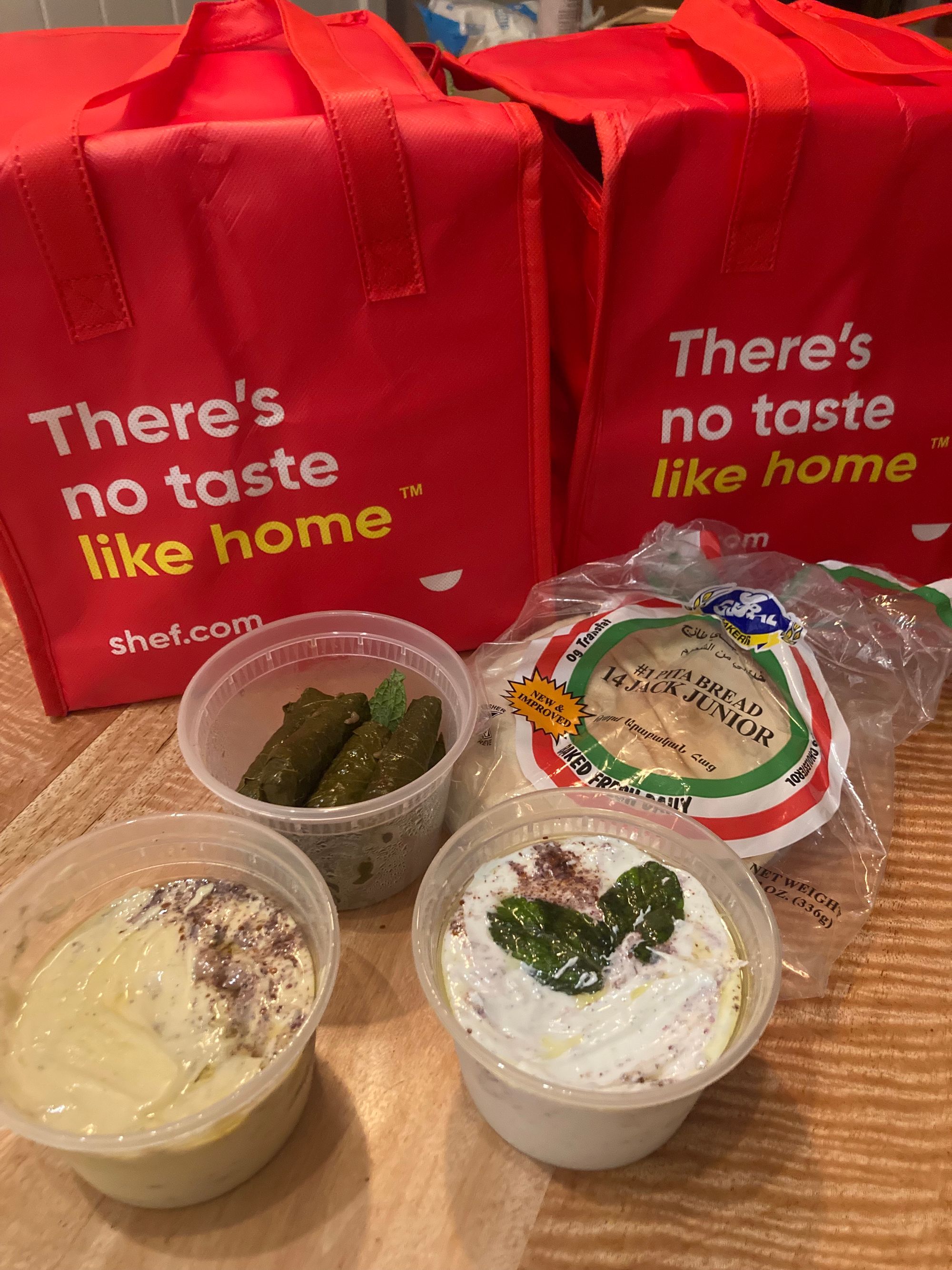

Beta tasting- Left: Homemade Middle Eastern hummus, labneh, and grape leaves Right: Homemade Lauki Dal Tarka and Green Butter Chicken (Source: HNGRY)

On Monday night, I placed an order from both Palestinean and Indian “Shefs” to be delivered two days later. Fast forward to my delivery day, I received a text from DoorDash Drive during my two hour scheduled window that allowed me to track where my order was coming from. Was it a house? A commercial kitchen? The driver showed up to my home with both chefs’ dishes in separate Shef-branded insulated bags with plastic containers kept cool by frozen bottles of water. I proceeded to drive 30 minutes down to the pin found on my DoorDash SMS notification to figure out exactly where my food was coming from. Turns out it was a former smoke shop with no kitchen attached. By creating an intermediary pick-up point for DoorDash drivers, Shef can not only consolidate its logistics to a single point of origin, but more importantly it can create plausible deniability about where its chefs are cooking from. In cities like San Francisco where the company was originally founded two years ago, Shef has gone so far as to lease empty commissary kitchens for the sole purpose of logistics. That way, if the health department ever investigates, the startup could claim that its chefs use its kitchen. But that reality is far from the truth.

HNGRY spoke to Akshay Prabhu who founded the original home chef marketplace Foodnome and was responsible for getting California MEHKO legislation passed under AB-626 three years ago. The startup was recently featured on David Chang’s new Hulu series on the future of food, “The Next Thing You Eat.” In the third episode, Chang and Prabhu talk about the future of home microenterprises while enjoying delicious quesabirria tacos from Barra de Pan, a licensed MEHKO open for sit-down dining in Riverside County.

“I started running pop-ups, I got shut down by the health department. I started lobbying, and created a permit for small scale restaurants in homes. Once the law got passed, you had to get county-by-county opt in,” he said in a phone interview with HNGRY.

Thus, AB-626 laid the framework for local county health departments to adopt legislation around MEHKOs, but it didn’t mean that anyone in the state could immediately apply for a permit. To add to the confusion, all 50 states have long had some version of a cottage food law that allows home chefs and bakers to make shelf-stable baked or dried goods (think cakes, cookies, dry pasta, jams, etc.) But these laws don’t include prepared foods that fall under TCS, which stands for “time and temperature control for food safety.”

In 2019, California state legislature added an amendment to AB-626 that exempted home chefs from the many stringent requirements of a typical restaurant such as commercial-grade hand washing facilities, limits to who can be in the kitchen (e.g. family members), temperature sensors for hot holding equipment, and so forth. While Foodnome’s 120 restaurants are all legally-licensed MEHKOs that deliver and serve hot food directly from home kitchens, Shef has its vendors cook and cool their food before dropping it off at one of its pickup hubs. According to a HNGRY Trends member who operates a nationwide meal prep startup, the risk of pathogen growth from chilling freshly cooked food is 3x riskier than that of naturally-cooled hot food delivery or takeout. Large vendors of refrigerated, pre-prepared meals like Freshly and supermarkets have HACCP plans with a dedicated team of food scientists and quality assurance staff to ensure food safety.

“Regulation and compliance are really important to me. For us, every chef is required to comply with all local laws and regulations,” said Co-Founder and Co-CEO Alvin Salehi in a phone interview with HNGRY. “I like to think of [legislation] as three categories: cottage food, food freedom, and MEHKOs. From a baseline that means that already this category is way ahead of Airbnb and Uber when they were in the same position. We already have some sort of framework in place... Many of the states are open to the idea of taking an existing framework and adding different types of food you can cook from home.”

Prabhu doesn’t buy the Uber/Airbnb analogy and has purposefully chosen to instead build a Shopify-like “business in a box” model that helps home chefs form an LLC, go through the proper MEHKO permitting process, and build their customers. The point is to enable the creator economy of food entrepreneurs to build a following that could someday parlay into a brick and mortar or food truck rather than create a gig economy for home cooking. Prabhu has gained intel on Shef from chefs who have churned over to his platform after getting fed up with their hub logistics model.

“Laws against food prepared from homes are explicitly against the books whereas Uber and Airbnb were in a grey area,” he explained. “[Shef is] able to cover themselves because it's delivery-only. The consumer never sees where the locations are. Cooks get all the orders for the day, drop them off at a commercial kitchen and DoorDash drivers pick up from that kitchen. They’re trying to blitzscale to as many cities as possible, they’re trying to see how quickly they can spread before they get caught. Some of the cooks are in commercial kitchens and most are not, they are being intentionally vague about it so they don’t get in trouble.”

If you study Shef closer, you’ll find top brass from the world of politics and corporate law. Salehi was a former technology advisor under the Obama administration where he founded Code.org, Shef’s general counsel Danielle Merida previously held a similar position at TaskRabbit, and Senior Counsel Stanley Chen worked on compliance counsel for Weedmaps.

When HNGRY spoke to public health offices in Chicago and Los Angeles, two cities where Shef currently operates, both representatives said that Shef’s meals fall outside of what is permitted under current cottage food laws. The same goes for the small handful of states that have enacted food freedom laws, which allow residents to sell almost any homemade food, aside from those that contain meat, without any license, permit, or inspection. While MEHKOs are subject to inspection, most local health agencies lack the manpower or desire to police any form of home chef due to their lack of staffing and the risk of Covid. In Los Angeles, one representative said that she received over 1,000 cottage food applications over the past year and a half. It is unclear just how many of those chefs are actually falling within the guidelines.

“Anybody who buys from these people is playing Russian Roulette,” she said.

Shef has a 150-step onboarding process which includes a food safety certification exam and food quality assessment. According to Prabhu, the platform only additionally requires proof of a food handler’s certificate before allowing chefs to begin cooking and chilling food.

“In their Terms of Service, [Shef] tells cooks they need to adhere to local laws, but they don’t tell you what the laws are. There’s a lot of the rules in the legislation that they’re not following,” he explained. “There are so many things in the food world around actually ensuring safety that these chefs don't know, because they haven’t worked in the food industry. Transparency is important and what I don’t like about it is that they are lying to cooks so that they don’t know they’re liable if someone gets sick or something goes wrong. Who's going to be bearing the brunt of the impact of that?”

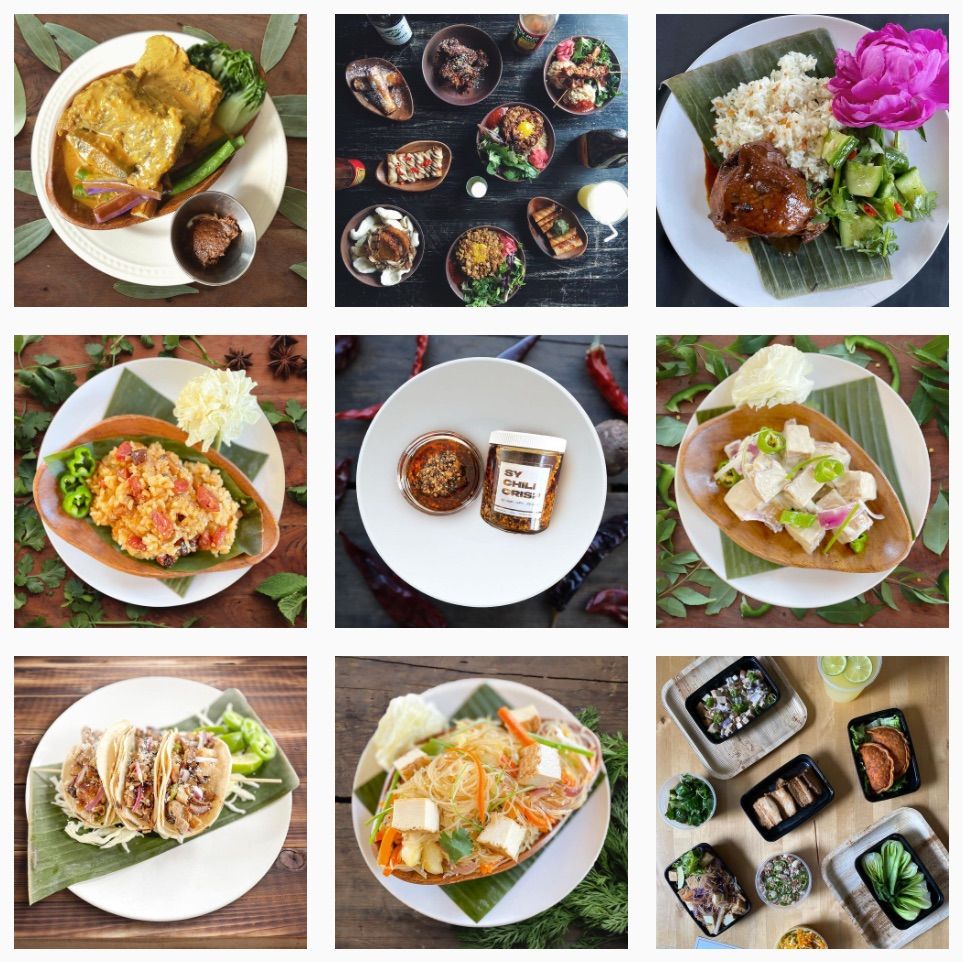

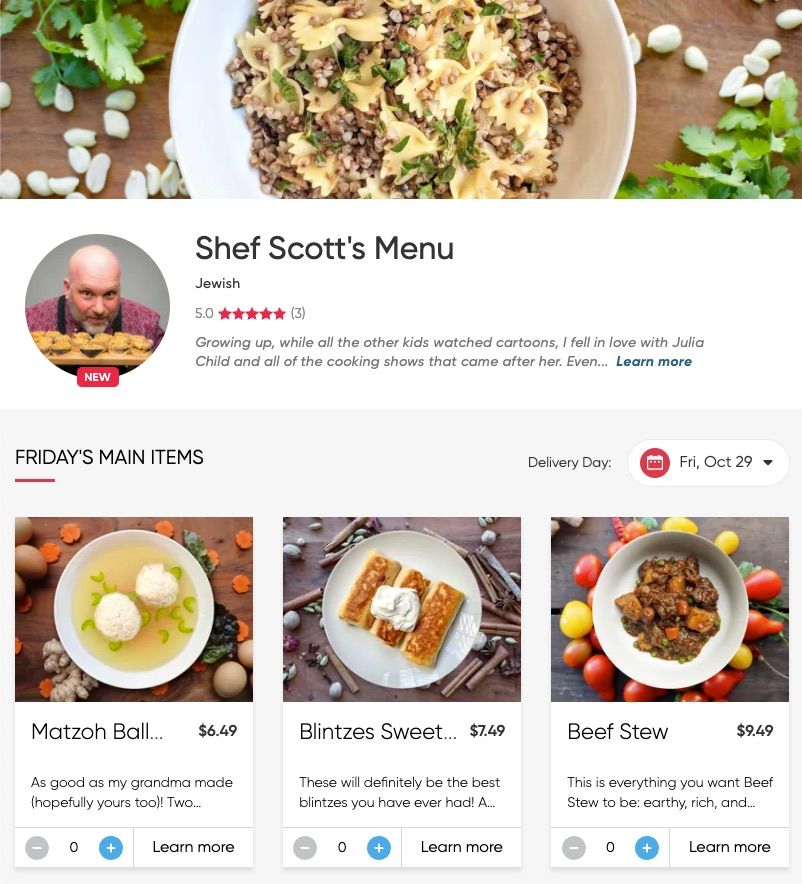

Regulation aside, platforms like Shef, Foodnome, DishDivvy, and the newly-incubated Castiron platform all lower the barrier to entry for aspiring restaurateurs and packaged goods upstarts while giving consumers a taste of something authentic and new. Most diners who have ordered from the platform are seeking out traditional ethnic cuisines that are difficult to come by on traditional delivery platforms such as Pakistani, Persian, or even Jewish comfort food (dare I say homemade Kasha Varnishkes and blintzes!?)

These platforms are largely centered around immigrants who are looking for non-traditional ways to earn side income doing what they love from the comfort and safety of their homes. On Shef, 85% of its chefs are people of color and 81% are female. Salehi says that the startup chose the name it did because it contains the word “she,” in tribute to founders’ mothers and the many immigrant women who leverage the platform as a way to take care of their families from home because they can’t afford daycare.

“When the Afghan refugee crisis happened, it really hit home for us,” said Salehi. “A lot of our founding story was helping these populations, and as part of that we opened the platform to refugees.”

Regardless of whether this is posturing or genuine, it is clear that these platforms are on to something. It’s just unfortunate that Shef might be putting the health of consumers and the liability of its chefs at risk in favor of growth.

“I think the mid-market restaurant will now be the domain of home,” said David Chang during the Foodnome cameo. “You get food delivered to that home you cook at home, but I think one of the things that will happen is that you’ll be able to serve food out of your home as a business.”

In time, legally. And hopefully before Shef has its first Airbnb-like catastrophe on its hands. For now, buyer beware.