Read Time

9 min

On Wednesday, I testified at New York City Council’s virtual hearing on a set of bills aimed to provide relief for restaurants during the pandemic, most notably focused on regulating food delivery marketplaces. In-house PR and government affairs directors from Postmates, Uber, Doordash, and Grubhub were all in attendance, unanimously fighting against 1908-A, a bill that would limit the delivery commission charged to restaurants by delivery platforms to a mere 10% and the marketing commission to 0% during a nationally declared emergency. Services like UberEats, Postmates, Caviar, DoorDash, and Grubhub charge 15% to simply list a restaurant’s menu on their apps without any delivery fulfillment and an additional 15% to use their couriers. On top of these commissions, consumers chip in to cover the high cost of delivery, which is still unprofitable for every marketplace except for Grubhub, which told its shareholders it will manage profits to breakeven this year. Cities like Seattle and San Francisco have already put 15% caps in place, with pending legislation in Los Angeles, Boston, and Chicago, the latter of which is considering setting a 5% cap. The fear, of course, is that this would cause the astronomical cost of delivery that is normally baked into menu prices to be finally exposed to consumers via a higher delivery fee, in turn imploding the market.

This battle is nothing new. Restaurateurs have begrudgingly used these delivery services to satisfy a growing piece of their business that has quickly become the sole lifeline during the current crisis. DoorDash has temporarily reduced delivery fees for independent restaurants by half and waived pickup fees, Uber has only waived fees for consumers and the restaurant commissions it charges for pickup orders, and, most egregiously, Grubhub has agreed to temporarily defer up to $100 million in commissions through March assuming that restaurants agree to stay on their platform for a year. The company has not yet collected any of these deferrals, but has been contractually able to do so as of April 13th.

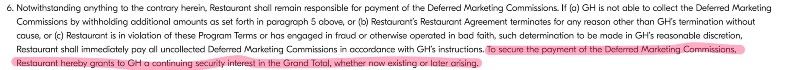

In her testimony, Grubhub’s Senior Director of Public Affairs Amy Healy referred to the $100mm in commission deferrals as an “interest free loan” despite the very clear fine print which states that “to secure the payment of the Deferred Marketing Commissions, Restaurant hereby grants to [Grubhub] a continuing security interest in the Grand Total, whether now existing or later arising.”

Councilmember Mark Gjonaj, Chairman of the Small Business Committee, has a history against Grubhub, New York City’s market leader with an approximate 62% share of the online ordering. Last summer, Gjonaj successfully called the company out for sneakily setting up websites and phone numbers that would hijack direct orders from customers searching for local restaurants and charge them bogus fees for referrals.

“Consumers are so used to convenience and paying on their phone that they don’t realize when they order through some of these apps how they are harming the businesses,” said Andrew Riggie, Executive Director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance.

In her statement to the Council, Healy vigorously defended Grubhub stating that restaurants have a choice in how they deal with the current crisis. “You can call a restaurant directly,” she explained. “That restaurant can choose to pay for their own delivery service, which we heard is expensive, or somebody can pick it up.”

In the beginning of her testimony, Healy expressed discontent with the federal government’s PPP loan program, calling it a “disappointing response” and stating “we have encouraged congressional leaders in the White House to do more. After that, we shifted to other programs to drive revenue, to drive orders to our restaurants.”

She then described the program in detail:

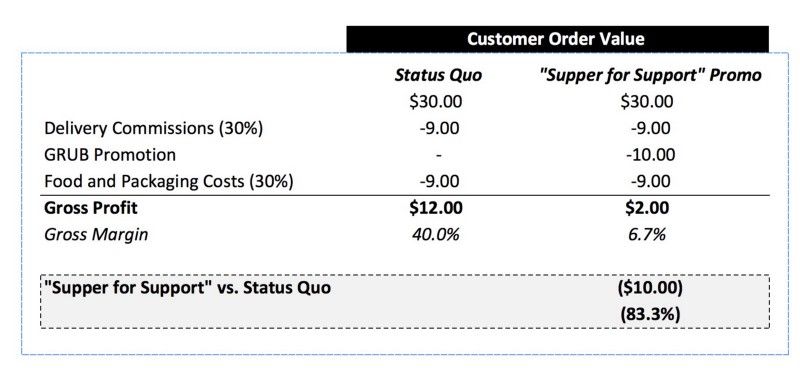

“It’s $10 to the restaurant to encourage a larger order, so if a customer will buy a $30 order we’ll give the restaurant $10 to increase the size of that order because bigger orders is better for the restaurant. That’s a $30 million cash injection to restaurants, it’s called ‘Supper for Support.’”

But under the promotion, bigger orders are certainly not better for the restaurant. It initially required businesses to eat the $10 discount and eventually pay full commission on the full, non-discounted order value. Dan Fleischmann, VP of the Kitchen Fund, put together the following model that explains the predatory nature of this campaign that would result in a significant 83% loss in gross profit compared to had the restaurant not participated in the promotion.

After a backlash of bad publicity, the company said it would dedicate $30 million to give each participating restaurant a $250 credit towards the equivalent of 25 discounted orders provided that they continue subscribing to the promotion, where they would be back on the hook to cover the $10 yet again. It is apparent that many businesses have a full grasp of the fine print.

“Do you think that restaurants have, with the various app options… negotiation power though? Or are they compelled to be on all the apps if they’re going to have a viable delivery business or they have to be on Grubhub,” questioned Andrew Cohen, Chair of the Consumer Affairs and Business Licensing Committee. “The thing that will motivate me to act is if I feel like the restaurants don’t have any choice in dealing with you guys.”

Healy stood firm in her questioning, stating that “restaurants have many options to drive business other than third-party marketplaces, none of which are seeing their fees regulated. The arbitrary cap would limit how restaurants, especially small ones, can market themselves and therefore limit how many customers and orders we can bring to these restaurants. Why not cap how much other marketing platforms can charge these restaurants? Why not cap Google or Facebook ads? Yelp, Yellow Pages, newspaper, radio, billboards– these are all marketing options that restaurants have.”

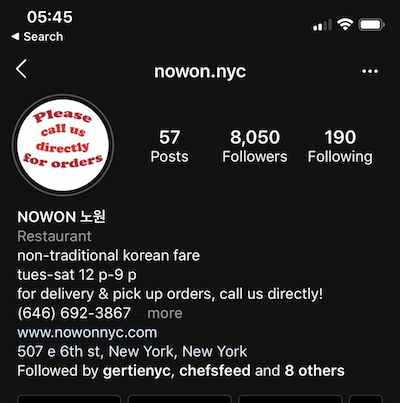

It’s never been clearer that online food delivery is unsustainable for both platforms and restaurants. Thus, restaurants need to figure out direct online ordering as soon as possible. The situation is so dire that restaurants like Nowon in East Village, Manhattan have changed their Instagram avatars to text stating “Please call us directly for orders.”

Restaurants must restrict their use of 3rd party delivery in order to solely use their last-mile fulfillment options like DoorDash Drive or Postmates’ API, which costs roughly half of what those marketplaces would charge if they both sourced and fulfilled the order. The clock is ticking.

Full testimony below:

April 29, 2020

Good evening Councilmembers,

My name is Matt Newberg and I am the founder and author of HNGRY, a new media platform that is dedicated to the emerging intersection of food and technology.

Despite having been only a few months since my last testimony, we have witnessed a decade’s worth of new developments. We are now officially living in a 100% off-premise society where takeout and delivery are the sole options for dining at our favorite restaurants. In a post-COVID, pre-vaccine world, there is no doubt that delivery and takeout will remain the dominant lifeline for restaurants. However, the chance of restaurants’ survival will continue to decline each day until the entire system is rethought.

In just a matter of weeks, restaurants have suffered a one-two punch– depressed sales, and on top of that, a rising percentage of delivery that accounts for those sales. According to a recent survey from the National Bureau of Economic Research, restaurant owners cite a 30% chance of remaining open through December if the current crisis lasts for four months. That probability quickly halves to 15% if it lasts 6 months. As Momofuku founder David Chang recently tweeted, “restaurants cannot survive off of take out alone,” referring to delivery as “fools gold.”

To explain why, consider an example from Patrick Hellstrand, CEO of successful vegan fast casual chain byChloe. If delivery accounted for a third of a restaurant’s sales yesterday and doubled to two thirds today, that same business would have to increase its sales by 50% to break even assuming a 30% commission to third parties. Compared to had it simply not done any delivery at all, that restaurant selling two thirds delivery would have to double its sales to just to break even. Thus, Hellstrand’s presentation to a room full of restaurant execs last November was titled “the zero-sum game of delivery.” Of course, this math was all done before the crisis and assumes a restaurant can make a healthy 15% margin on dine-in. But the principles remain: the more delivery sold through third party apps like Grubhub, DoorDash, UberEats, and Postmates, the worse the restaurant’s bottom line.

An example that turns zero-sum into downright unprofitable is Grubhub’s “Supper for Support,” a controversial promotion that takes advantage of restaurants that don’t read the fine print. The scheme offered consumers a $10 discount, beared by the restaurant, while it simultaneously charged them the same 20–30% commissions of the full order value– non discounted. If you do the math, a restaurant would have to pay out $22 of a $40 order to Grubhub for fees and discounts. That’s a 64% reduction of profit vs. had it not participated at all. After getting flack, the Grubhub responded by setting up a $30mm fund to provide each of these restaurants $250 each to continue the abuse. I want to quickly share my screen to demonstrate these economics.

When restaurants are allowed to reopen at half capacity, the lucky few who can muster up a makeshift operation will still bear a heavy loss. Every idle seat is a cost center absorbing overhead of rent, labor, and utilities. Profit margins are zero until you cover these fixed costs. According to Bo Peabody, Executive Chairman of Seated, a restaurant reservations rewards app, average national occupancy for full service restaurants pre-COVID was 46%. If that benchmark was already unsustainable, now you can simply halve it again. How will restaurants operate at a quarter of occupancy, half of what they’re used to, while being forced to sell 50% or more via delivery just to cover their expenses? One may think an easy solution to allow restaurants to make money off of delivery would be to naturally restrict the commissions that delivery apps charge.

However, despite their current high percentages in the 20–30% range, delivery remains highly unprofitable for all of the major delivery marketplaces. It’s simply a game of the “last man standing.” Under its January level of burn-rate, DoorDash has only 9 months left of runway. Postmates is slightly longer at 11 months.

So what’s the solution? I don’t have the answer, but I will leave you with this.

It’s clear that if the economics of owning a restaurant were unfavorable before this crisis, then they must now be unimaginable. Thus, we must rebuild from the ground-up, enabling our local restaurants to own more of their customers through direct phone, web, and mobile ordering as opposed to paying a thirty-cent tax on each dollar to deliver to the very customer who used to sit down and pay full price. To survive, restaurants must start moving as much business on to their own white-label delivery platforms like Chownow, Lunchbox, and others and away from DoorDash, UberEats, Grubhub/Seamless, and Postmates. They can, however, still use DoorDash, Uber and Postmates’ logistics services to handle the delivery part for a much lower percentage than their high marketplace fees.

Some of these companies have deferred payment of these fees or temporarily waived with no guidance on future plans, because it is painful to ask the fundamental question today that may lead to a conclusion that excludes them altogether tomorrow. That question being: as a restaurateur, would I have been better off by not participating in this game at all?

Thank you.