Read Time

4 min

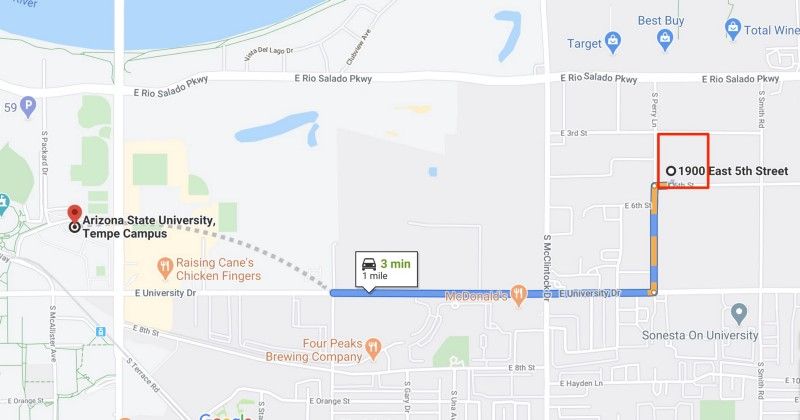

Since last summer, CloudKitchens has been aggregating independently owned food trucks to launch new markets faster than the lengthy construction process required for its multi-kitchen warehouses. In lieu of leasing space to restaurant tenants to occupy 225 square-foot kitchens, the company sells its Otter software to food trucks intrigued by the promise of selling on all the major third-party delivery marketplaces. Not only does this help CloudKitchens launch faster, but more importantly, it helps them figure out what sells best before restaurant tenants sign leases in their kitchens. The test is happening in an industrial parking lot of a future CloudKitchens site under construction in Tempe, AZ, conveniently located just minutes away from Arizona State University. According to plans filed with the city of Tempe, the lot is designed purely for delivery drivers, not diners.

Truck owners pay a monthly fee of $350 plus a 15% commission (on top of delivery marketplaces) up to $650, for a total guarantee of $1,000 per month. That gives them the ability to show up to the parking lot at any time, use a single tablet that’s integrated with all the marketplaces, and receive additional orders from CloudKitchens’ tested “facility brands” that it reuses across a handful of locations. Trucks pay a 10% commission on top of the normal marketplace commission on those incremental orders. CloudKitchens provides trucks with power, greywater removal tanks, and porta potties for staff.

In reality, its Otter software is very much a trojan horse for food truck and kitchen operators. Just like Amazon leverages marketplace data to compete against other sellers with its AmazonBasics products, CloudKitchens is able to mine sales data from its kitchen tenants and trucks to form its own brands that it controls. For example, SuperTruck not only sells under its own brand but also makes food for CloudKitchens’ “facility brands” like “B*tch Don’t Grill My Cheese” (tagline: “All sandwiches served with a side of bad attitude”) and “Late Night Munchies.”

Another truck owner, Wok This Way, sells under a CloudKitchen owned brand titled “Phuket I’m Vegan.” In LA, this brand is operated by another CloudKitchen tenant, Salathai. If this sounds like BuzzFeed clickbait for food, it basically is. CloudKitchens has A/B tested these concepts on third-party marketplaces, found which ones resonate well with college students, and are getting a 10% royalty on every item sold without lifting a finger.

“If you’re an ASU kid and you’re partying, studying all night and it’s 5am and you go online and you find ‘Egg the F*ck Out’ you’re like hell yeah,” explained an anonymous food trucker who no longer works with CloudKitchens. “They don’t care where they’re getting their food.”

There are somewhere in the range of a dozen trucks signed on, with 3–4 on site during lunch and dinner hours spanning into the wee hours of the morning. The strategy is similar to Reef Kitchens’ parking lot trailers, but with less permanence. Many of these trucks have already parted ways with CloudKitchens’ after seeing a lull in sales during periods like summer, when there’s naturally less demand but CloudKitchens can easily replace them with another operator that’s eager to test out a new sales channel. CloudKitchens sets up all the listings under its own accounts and doesn’t seem to remove them from third party marketplaces once the trucks leave. A much more optimistic truck operator explained there was a benefit to being able to pull into the lot after a major event and sell leftover food.

“Ultimately, you’re just working for them,” my truck owner continued. He explained his desire to brand and promote the lot for foot traffic, where the company wouldn’t be able to capture any offline sales, was beginning to cause tensions with CloudKitchens’ management. “Food truckers are food truckers because we don’t color inside the lines. We have our own kitchens because we don’t want to deal with the BS of the tech/corporate world.”

Many of the truck owners I spoke to were surprised to hear that the company had a provisional license to host food trucks until the construction was complete. Some were told that they would be given a preferential rate to lease a proper kitchen once the facility was open. None knew the associated costs and gross sales requirements to break even in a ghost kitchen.

“I think the ghost kitchen concept is the way of the future, but there’s gotta be a better way,” said the truck owner. “They didn’t think it through. Food trucks are the one that suffered. I don’t think we pulled the sheets over our eyes too long.”