Meet the entrepreneurs turning restaurant delivery into airport food

November 21, 2019

Read Time

6 min

As evidenced by DoorDash and Uber’s foray into ghost kitchens to compete with Cloud Kitchens, more tech companies are inching their way towards becoming modern day restaurateurs, a skill for which they have no proven competency– yet. However, there are two companies taking it a step further through a new approach they’re calling “franchising 2.0.”

Following the recent announcement of the $400mm investment from the Saudi Public Investment Fund into Cloud Kitchens, another startup, Virtual Kitchen Co, announced its $15mm investment last week led by Andressen Horowitz (and an additional $35mm of debt to purchase and convert properties into virtual infrastructure). The company is founded by ex-Uber employees and is attempting to apply a virtual franchising model to food delivery. They are betting that national brands will entrust them to cook their best-selling items on third-party delivery platforms in markets where there’s untapped demand in exchange for a single-digit percentage royalty fee. It’s a foodservice model that’s been pioneered by the likes of Aramark and Sodexo for campuses and OTG for airports. As anyone who’s eaten at an airport version of a restaurant can attest, these outlets are not 1:1 with the experience you would normally have at an owned and operated location. Foodservice companies source commodity ingredients, hire their own cook staff, and prepare food on behalf of licensed restaurant brands.

This week, I attended Kitchen Fund’s Restaurant of the Future, a roundtable discussion with the CEOs of by Chloe, Kitopi, Sharebite, and Checkmate. Kitopi has a similar model to Virtual Kitchen Co and has raised $89mm for its operations in London, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and now, Brooklyn.

“Our view is that no one should own kitchens, not just at home. No hotel, no restaurant, no one should own kitchens,” explained Kitopi CEO Mohamad Ballout to a room of restaurant investors and operators. “If you want to have an experience center, that’s great. We think the evolution of food is one where everything into production of food is done offsite in a much more efficient environment.”

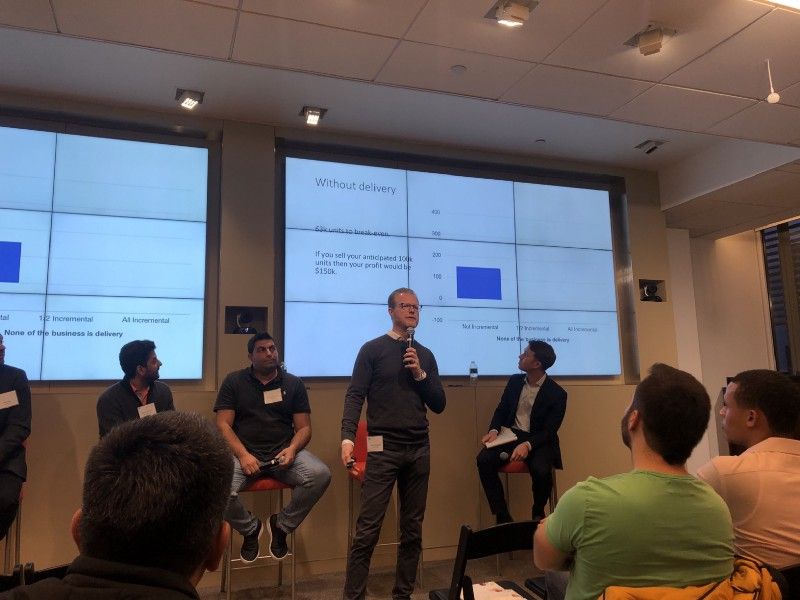

Patrik Hellstrand, CEO of by Chloe, walked the audience through a presentation outlining why today’s food delivery model is a zero-sum game for restaurants, a notion that operators are increasingly waking up to. Under his scenarios where a $1mm revenue-generating retail location operates at a 15% net margin, delivery sales would cannibalize profitability compared to a scenario without delivery. This holds even if half of those customers were newly acquired from the delivery platform (vs. existing customers of the restaurant ordering on delivery apps).

“As your share of business of delivery grows, the need for it to be more incremental grows as well. Intuitively, you would think if delivery grows, the ‘incrementality’ probably reduces,” said Hellstrand. “This is why I call it a zero sum game.”

However, startups like Kitopi and Virtual Kitchen Co are actually incremental, as they allow restaurant brands to scale nearly overnight to an entirely new delivery radius where they don’t currently exist. These startups and their investors draw analogies between food and software, likening themselves as highly scalable kitchen infrastructure and operations akin to Amazon Web Services or Shopify, but for restaurants. As a carnivorous consumer, imagine a Katz’s Deli pastrami sandwich magically available on demand in LA or an In-N-Out Double Double on demand in NYC. As a restaurant owner, imagine being able to test your brand in a new market without spending hundreds of thousands on a new retail location that could easily flop.

The first part of the stack is the bare-metal kitchen infrastructure (which Kitopi leases and Virtual Kitchen owns), the second layer is the operating platform where orders are aggregated and prepared, and the third layer is content. Ballout repeatedly referred to his partner restaurant brands as “content” on top of his scalable kitchen platform that can get brands up and running in weeks with minimal upfront cost compared to building out their own retail. Kitopi charges brands an onboarding fee and pays them a 10% royalty on all sales. After its labor, royalty, food costs, and production overhead it claims a 10% contribution margin, about 5% lower than a healthy restaurant operation Hellstrand outlined. Naturally, the startup must have its sights on a larger vision to warrant its recent $260mm valuation.

“Our view is that the cost of entry in the food space is so low that, unfortunately, we think that content is going to be less valuable comparative to the hospitality or airline space,” said Ballout. “We’re seeing that already happen.”

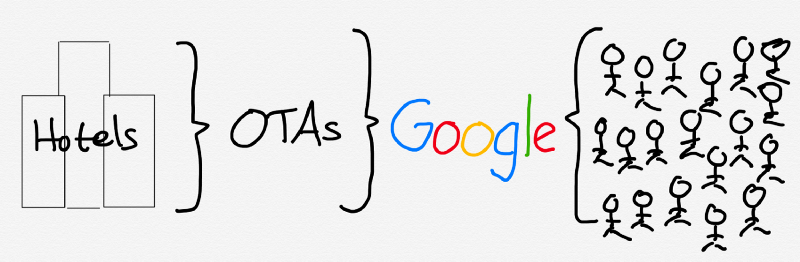

There have been many parallels drawn between aggregation theory and food delivery marketplaces. The concept, which has been used to describe everything from Amazon to Netflix to Google, states that in many industries like travel, music, and e-commerce, aggregators have stolen hundreds of billions of dollars of value from those markets by simply owning the end customer relationship and plugging into a vast supply network with next to zero transactional costs. Hellstrand disagrees with the notion that restaurants can fit into a similar analogy. Unlike Netflix, Airbnb, or even vacant hotel rooms, the marginal cost of serving an additional customer is material.

“It doesn’t work that way in restaurants, unfortunately,” he explained.

In theory, if Kitopi and Virtual Kitchen Co can convince enough popular brands to hand over their recipes and automate their production, they could conceivably wield enough leverage to drive labor costs down with robotics and lower food costs by increasingly commoditizing the supply chain. The “content” layer is just slapping labels on sandwiches, salads, and other highly modularized food items. Cloud Kitchens is already ahead of them on the pizza front, as Travis Kalanick is rumored to serve on the board of Family Style Inc., founded by DJ Steve Aoki’s manager. The group operates a handful of delivery-only pizza brands like Pizzaoki, Froman’s Chicago Deep Dish (a nod to Ferris Beuller), and Lorenzo’s of New York not only from Cloud Kitchens’ facilities, but also distressed strip mall kitchens formerly belonging to ethnic restaurants. Last month, the company partnered with the creators of AMC’s Breaking Bad to use its Los Pollos Hermanos brand from the show to do a pop-up virtual delivery brand under the very same name.

“Our view is that no one should own kitchens, not just at home. No hotel, no restaurant, no one should own kitchens.”

Family Style had previously licensed the legendary Joe’s Pizza brand, but HNGRY confirmed with Joe Vitale, ex son-in-law of the original NYC owner Pino Pozzuoli, that he is no longer working with the group. Vitale is currently looking to expand locations of his own, which would have violated his franchise agreement with Family Style. See how all of Family Style’s pizzas are made by the very same employees, equipment, and ingredients within Cloud Kitchens in a scene from HNGRY’s debut episode, 001. fast(er) food, below:

For the entire equation to work, global restaurant brands must entrust technologists with their tried-and-true recipes in a highly volatile environment of food delivery. Consumers’ interest in that brand must translate to a certain price, quality, and level of convenience that will drive repeat purchase. But then, even if the experiment does prove to be successful, restaurants would naturally want to capture more of the value for themselves, leaving Kitopi or Virtual Kitchen Co to open their own delivery and retail locations just like Joe did. Therefore, it wouldn’t be farfetched to view these startups as experimental retail platforms rather than long-term restaurant franchise partners.

“We believe in removing the art out of the kitchen,” said Kitopi’s Ballout. “Some chefs are not comfortable with that. We think the only way to be efficient in the kitchen is to keep it driven by science rather than art.”