Read Time

4 min

The following is a guest opinion piece from HNGRY Trends member Ashwin Wadekar, Director of Global Strategy at Gorillas.

“If something sounds too good to be true,” the saying goes, “it probably is.” So when a virtually unheard of industry explodes with a suspiciously enticing promise - 10 minute groceries! - it is tempting to think something is amiss.

At least Bloomberg and The New York Times think so, with both publishers eying the quick commerce boom with considerable skepticism. These pieces center on three core arguments. First, quick commerce upends city life by displacing small businesses in the name of convenience. Second, it pushes more of the labor force into a ruthless delivery economy. And third, the model itself - smaller, widespread formats, and the daily purchasing behavior that comes with it - is wasteful.

There is surely room to consider the way in which quick commerce should interact with the local community. But fundamentally, the rise of quick commerce deserves to be celebrated rather than reflexively disparaged.

The primary argument outlined in Bloomberg is that “our post-pandemic urban future is less likely to be one where we’re on a first-name basis with the neighborhood baker than one where the streets are filled with workers ferrying cilantro for impromptu tacos.”

This dystopian and highly exaggerated view of quick commerce misses key points. Though early in the industry’s life cycle, it seems that quick commerce is taking share from national chains more so than independently-owned stores. Yet, the decline of big box retail was in full force even before the pandemic, and certainly well before quick commerce. Those who live in major cities know well how chaotic grocery shopping can be (and New Yorkers, at least, have grown accustomed to queuing simply to enter the store). Inside, the experience is no better, where an entire grocery run can be derailed on account of one or two missing ingredients. It is no wonder that quick commerce has taken off with such force.

The average grocery store sells something around 20,000 SKUs, whereas a typical quick commerce fulfillment center will carry closer to 2,000. What happens when the highest-volume sales items move to quick commerce? You may still have to supplement your shopping, but these items will be in the long-tail: specific spices, maybe some uncommon produce.

Just the other day, I did most of my grocery shopping through Gorillas but still needed cardamom for a recipe. Instead of waiting in line at a large-format supermarket for a couple of ingredients, I opted for the local Vietnamese market in my neighborhood. So far from stifling cultural hubs, quick commerce can complement and even bolster these neighborhood institutions. And who knows? Maybe it can spell the end of the infamous “ethnic aisle.”

Beyond retail, quick commerce can amplify local brands and help them serve customers they wouldn’t otherwise have been able to reach. Gorillas has used its extended footprint to help take a handmade purveyor of nut butters from a local Berlin outfit to a widespread audience across Germany. In New York, Gorillas promotes a different local partner as a part of a weekly giveaway to all customers. To commemorate Juneteenth, we spotlighted ice cream bars from Island Pops, a Brooklyn-based Black-owned brand.

Perhaps the most frustrating argument, touched on by both The New York Times and Bloomberg pieces, is the one around labor. In the US, where employment and healthcare are necessarily tied, full-time benefits are provided to full-time riders. The same goes for requisite equipment: bikes, phone stipends, rider gear. At the same time Hurricane Ida ravaged New York City, killing 13, food delivery companies lured couriers with sticky financial incentives to ensure demand was met. Meanwhile, Gorillas and other quick commerce companies shut down local operations to protect rider safety.

When DoorDash launched its competing ultrafast delivery service, it had to do so with its own labor force - a monumental strategic shift for a company that has built a $50B business on contracted labor. It is undeniable that some will continue to prioritize flexibility over stability, and so there will likely always be a place for the gig economy. But the future of delivery probably looks more like a blend of multiple labor models rather than a heavy reliance on just one. Quick commerce has initiated the power shift back towards direct employment, and that deserves to be celebrated.

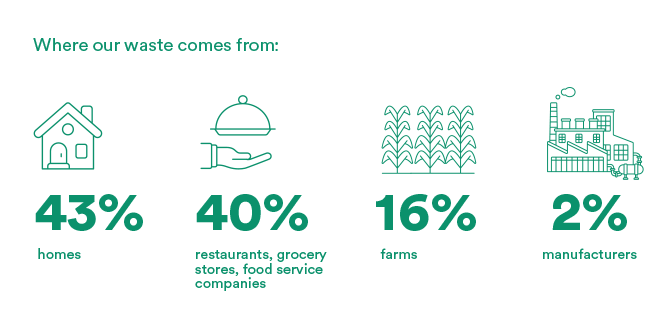

Finally, quick commerce facilitates more sustainable consumption behavior. Approximately 40% of food is wasted. US food retailers waste 10.5M tons every year, and 35% of that waste goes to the landfill. Retail food waste is such a major issue that California now requires retailers to donate surplus food to food banks or similar organizations. But an even bigger issue exists at the consumer level, where individuals simply buy more food than they end up consuming.

Moving to smaller footprints and encouraging daily purchases solves both problems. At the retail level, it allows for smarter and more nuanced demand planning, since each micro fulfillment center serves fewer people than a traditional supermarket. At the consumer level, the immediacy changes purchasing behavior and can reduce consumer waste. No need to stock up on food you may not need when an order is only minutes away, waiting to be delivered sustainably on an e-bike. You buy what you need, when you need it.

Competing interests will manifest. Regulators will have to determine how to balance multiple stakeholders and solve hard questions. (For example, bike lane infrastructure must improve in many cities in order to ensure the safety of all riders, delivery workers included). But rather than viewing quick commerce as an enemy to stifle, local authorities should consider the broad set of benefits that this model provides.

Brick-and-mortar retail survived e-commerce, and now both channels will have to find an equilibrium with quick commerce. The rapid consumer uptake is alone evidence that the old model was in desperate need of disruption. So when Gale Brewer, the Manhattan borough president, asked the rhetorical question to The New York Times - “who the hell needs an apple in 15 minutes?” - the answer is clear.

Apparently, millions.