Personalized Nutrition Deep Dive With Dr. Casey Means of Levels

August 20, 2020

Read Time

27 min

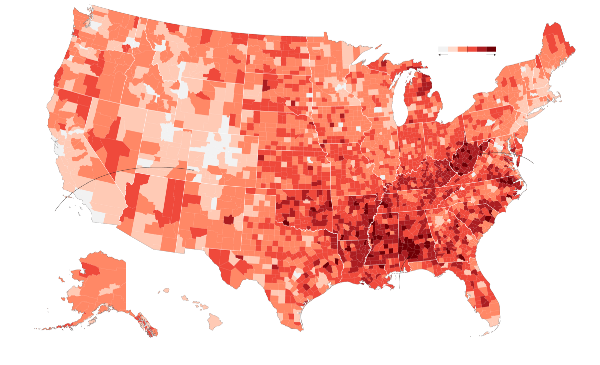

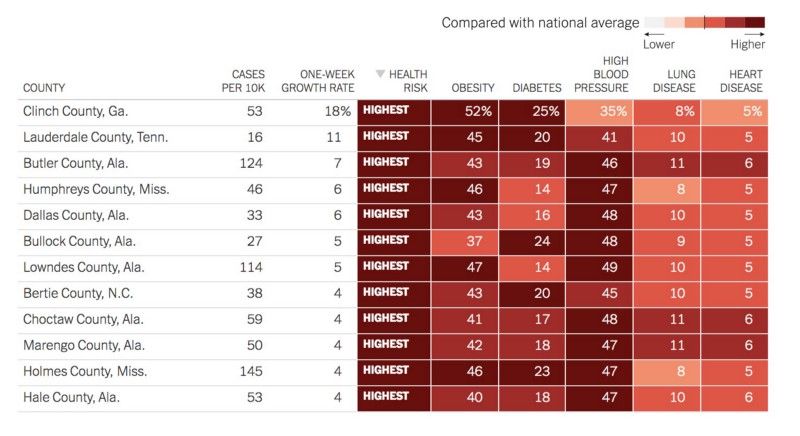

97% of Covid-related deaths are associated with obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. Americans cannot afford to continue to shut down our economy and overwhelm our healthcare system each time we face a new pandemic.

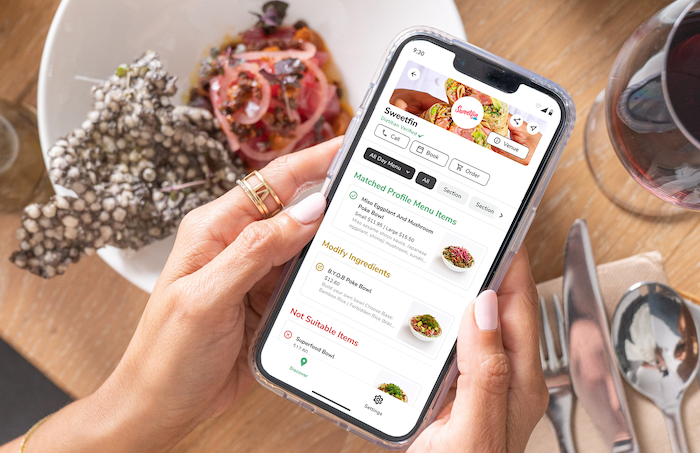

Dr. Casey Means, co-founder and Chief Medical Officer of Levels Health, believes that metabolic health is key to warding off chronic diseases that make us more vulnerable to viral outbreaks. Levels empowers individuals to radically optimize their health and wellbeing by providing real-time continuous glucose biofeedback coupled with machine-learning driven insights to inform personalized diet and lifestyle choices. The startup offers a 1-month “metabolic awareness journey” that combines glucose sensors, smartphone health data, and nutrition logging to bring transparency into how our diets, sleep, exercise, and stress response impact our insulin levels.

Our interview below was edited for (slight) brevity.

Matt:

I’m curious if you could share a little bit about your background and talk about why you’ve chosen to focus on metabolic health and explain why that is such a crucial function that has been so overlooked.

Casey:

I’m a medical doctor. I trained as a head and neck surgeon before shifting to full steam ahead with digital health. I was at Stanford right at the end of the Human Genome Project when 23andMe and D2C genetics companies were coming online. As a college student, I was very much in the mindset of “the human body is this unique biochemical blueprint,” but the difference between health and disease is environmental inputs like food and lifestyle. Personalized genetics was just so under the radar at that time and that was a very empowering type of viewpoint because it really put the agency back on the individual, [in that] the decisions that you make are going to be the difference between the expression of health or disease.

I worked at 23andMe in college and ultimately went on to medical school, [which] is very different from that philosophy. Medical school is very much about pattern recognition. The way that traditional medicine is done is, you talk to a patient, you ask questions, you do an exam, and you get lab work or imaging. You put together this collection of signs and symptoms; symptoms being subjective, signs being objective. When those are packaged together, you call it a diagnosis and then you turn around and you say, “for this diagnosis, I’m going to put this medication or this surgery on that. And then we’re done.” That’s the antithesis of more of the personalized type of medicine that was emerging more in the research and industry side of things. Some people say that it takes 17 years for new research findings to make it into clinical practice.

Matt:

Wow.

Casey:

There is this major delay there. So it’s sort of disheartening that I was looking at things like “how can we leverage environmental stuff to express health?” You only get about four hours of nutrition in all of medical school, even though the vast majority of our healthcare costs and our healthcare conditions are related to diet. So fast forward, I train to become an ear, nose and throat surgeon. And a lot of the conditions I was seeing in surgery were inflammatory in nature. This [was] very strange, and when you step back, it’s like, “why am I treating an inflammatory disorder with surgery?” That’s fighting a battle with the wrong tool, a complex underlying physiology that’s ultimately based on the immune system. Busting a hole in the sinus, essentially plumbing, is not going to fix it. You’re seeing all these patients come back over and over for revision surgeries and it just became clear to me–– I wanted to focus on why my patients are becoming inflamed or why is everyone dealing with chronic inflammation? Couple that with the fact that these chronic conditions that we’re seeing just crop up all over the world like obesity, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s; these are also inflammatory conditions.

So, there’s something going on. When you step back and dig into it, that something is that our poor little bodies are being exposed to all these food compounds, “frankenfoods,” and environmental toxins, sedentary behavior, sleep deprivation, and chronic low-grade stressors that we as a biological organism don’t know how to process. These are factors of the modern world, and it’s causing our bodies to be in constant threat mode.

I left the surgical world and decided I really wanted to focus more on longevity medicine and prevention. I got really into the systems biology and network biology movement, which is this is the idea that with proteomics and whole genome sequencing, we can now start to understand the links between diseases as opposed to looking at disease as an isolated silo. Depression, prostate cancer, anxiety, arthritis, hypertension — we think of those as isolated silos but when you start actually mapping them onto the underlying genetic or physiologic connection, that’s network and systems biology. When you treat at that level, all of a sudden you’re really efficiently managing potentially multifarious diseases by just focusing on one pathway that connects them. So I think that’s the future of medicine and when you look at what the connection is between most diseases these days, it’s metabolic dysfunction, it’s high blood sugar, it’s insulin resistance. It’s the metabolism essentially being screwed up and it makes sense because metabolism fundamentally is the cellular machinery and the cellular mechanisms that generate energy from food.

When those processes are problematic, cells are not getting the energy they need, and that can show up anywhere in the body as very seemingly disparate symptoms that are actually rooted in the same physiologic process. So all that’s to say that it became very imperative for me to fix metabolic dysfunction as a root cause of inflammation, as a root because of so many pleiotropic chronic diseases, and that became my mission. But you can’t just tell a patient, “go out there and fix your metabolic dysfunction.” Ultimately, it comes down to thousands of choices we make every single day about what to eat, when to eat, how to pair foods, whether to exercise, when to go to sleep, how to respond to stress.

It became clear that this had to be a behavior change tool not a new approach to medicine. This isn’t about having more doctors tell more patients to get healthy, it was about empowering patients with a tool that would let them be healthy. That’s how I got focused on starting a company in that space, and that’s where Level’s emerged from.

Matt:

Do you think that the incentives are perverse within the existing healthcare system that enable this very prescriptive surgical approach to everything, or is it just simply the fact that technology has just yet to really catch up? Because at the end of the day, you can look at doctors like car mechanics where it’s like, okay, I’m going to inspect your car. I’m going to see this dent and I’m going to just charge you for this line item, this part, installing that part, and we treat everyone like they’re a broken car.

Casey:

Yeah, because if you start imagining that there’s a new fleet of cars that never break down, all of a sudden a lot of mechanics are out of work. So, I think that it is rooted in the economics of healthcare but I don’t think in a malicious way. I think it unfortunately is a system that started rolling and unfortunately we’re now bearing the fruit of the way the system was designed. This system ultimately arose from the fact that 50, 60 years ago, we set up a medical billing system that was based on codes. To get paid for a medical service in a fee-for-service system you had to bill, code a diagnosis, and then bill for your services. So those two things right there create a huge problem because all of a sudden, now you have to have diagnoses and you have to do something to get paid. That is really antithetical to the idea of a systems biology or really biochemically-based rational approach to physiology because it’s very reductionist. You have to put on a label on an individual problem for it to be real, when in reality, there may be an underlying physiology like inflammation that’s actually leading to eight different diagnoses but you cannot code for inflammation. There has been a lot of progress from this fee-for-service system which really has a bias towards reactionary action and what we’re seeing now, which is a movement towards value-based care. The idea behind value in medicine is that there’s this equation which is essentially outcomes over cost. You want outcomes to be really good and cost to be really low, and that would be a high value intervention.

So it both supports the patient and the bottom line. Obamacare proposed a lot of this value-based care type stuff but it’s going to be a long time until that is really embedded in our system. Ultimately, dietary and lifestyle are the highest value interventions. They have really good outcomes and they’re really low cost but right now, that’s not what pays, it takes time and upfront investment. As the system moves more towards value, I think we’ll see more focus on investing the upfront time and energy in behavior and lifestyle. Unfortunately, you’ve got two big factors that right now don’t work in this favor: one is the food industry and one is the healthcare industry. The food industry wants to make money and so right now, consumer demand is for highly addictive processed foods that cause disease.

They’re not incentivized to change things. The healthcare industry is also in a bind. Doctors have to see enough patients to make money. I’m not going to wait for these gigantic titanic-like industries to change when the incentives right now are very misaligned. The beauty of using continuous glucose monitoring as a behavior change tool is that it breaks down this entrenched barrier between patients and their own health information. It’s very difficult to get access to your own health records, a CGM (continuous glucose monitor) gives the data to the person 24 hours a day.

Suddenly, the healthcare system and the food system cannot dupe people anymore. You eat a cookie that is marked as healthy, and you know exactly whether it’s healthy for you or not healthy in 20 minutes. There’s no more pulling the wool over the eyes. It’s great in that way that it empowers the individual but data without knowledge and wisdom can potentially not be very helpful. I think the theme here is the software overlay that educates people. What does this data mean? How do I interpret it? How do I make real meaningful changes? That’s where Levels comes into play is take the data stream and make it super actionable for people.

Matt:

That’s awesome and really empowering. I’m curious if you could explain what the journey of the food as it enters our digestive tracts, and how our gut microbiomes play a role in digesting that food, storing glucose or releasing it, and then how that relates to continuous glucose monitoring.

Casey:

Long story short, metabolism is the set of cellular mechanisms that generate energy from our food and environment in order to power basically every single cell in the body. So, every cell in the body requires cellular energy to function, and efficient metabolism is just foundational for all these cells to work and for health, essentially. When we eat and digest foods, we take in fats, carbohydrates, proteins, micronutrients, and these are released into the bloodstream. Fats and carbohydrates are both big contributors to how we generate energy in the body. When carbohydrates are broken down, they generate glucose in the blood. Glucose is this molecule that our cells take in, and then it’s converted into a form of energy that we can use called ATP and that’s done in the mitochondria. The body works super hard to keep glucose in a really tight range in the bloodstream. It does this by releasing a hormone [called] insulin from the pancreas, which essentially floats in the bloodstream when you have excess glucose and binds to the cell membranes. That lets the cells take up the glucose to be converted into energy and when there’s an excess of glucose, some of that energy is either stored as glycogen in the liver and in the muscle, or if there’s even an excess above that, it goes into long-term storage, which is fat cells.

The more glucose we have in our bloodstream, the more insulin that’s released. The cells will see all this insulin and say, “oh my gosh, this is too much insulin, we’re going to stop responding to it, we can’t fit any more glucose in the cells, so halt.” That’s a process called insulin resistance, [where] insulin levels in the blood rise and the cells are less responsive to it. There’s evidence that 88% of Americans are insulin resistant right now.

You really want your metabolism to be running super efficiently. You move in the wrong direction of insulin sensitivity as you constantly spike your glucose in your bloodstream and spike your insulin, but you can improve your insulin sensitivity by keeping your glucose relatively stable, not causing huge spikes. Ultimately, keeping your insulin exposure down and your cells will regain their sensitivity over time. That’s very positive for the body.

The insulin resistance is the chicken and the glucose rising is the egg and the more you spike over time, over and over and over again, the more you’re becoming insulin resistant.

Matt:

Does that create a flywheel effect for people to just get hunger pangs after they’ve just consumed a burger, fries and Coke to want to eat a snack two hours later? Is there a compounding effect of this flywheel where I’m becoming hungry or thirsty and I need another hit?

Casey:

Totally, yes. So what happens when you spike and you get this big insulin surge, you basically overcompensate. Your sugar will crash down, because you released all this hormone. It gets sucked up by the cells and now, in your blood, it looks like you have low blood sugar. Sometimes you see a spike and a dip where it comes back to normal and that’s called reactive hypoglycemia, which means huge surge, huge drop, and then you come back to normal and that’s usually associated with hunger.

So it’s actually a lot better to just have gentle rolling hills in your glucose, because you’re never going to over-surge your insulin, have a glucose crash, and then feel this need inside your body to get it back up there by having another snack. The other thing that’s interesting about insulin — this is the key point — is that insulin signals to the body that you have energy from glucose. It says, “You just ate a bunch of glucose, so you don’t need energy from other sources at this moment.” It actually tells your body to not burn fat for energy. Insulin totally blocks fat burning so this is why there’s this relationship between eating sugar and gaining weight because when you’re eating sugar all the time, your insulin is high and you cannot burn fat. I think we live in a country where we, at scale, cannot burn fat because we’re constantly eating refined carbs and grains and so, I bet these bad oxidation pathways that are really meant to be there for a survival advantage for us are just not being utilized.

Matt:

So, I’ve been playing around with the FreeStyle Libre. It was recommended to me by a guy named Richard Sprague, a biohacker who has been doing lots of microbiome tests on himself. He suggested I get on this bandwagon. He didn’t tell me what to do too much, I just started messing around with it.

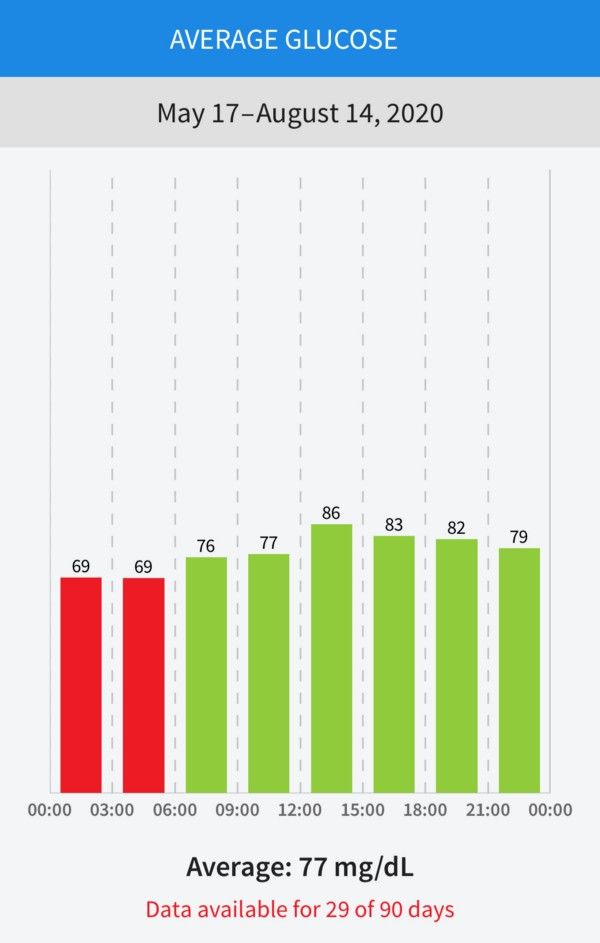

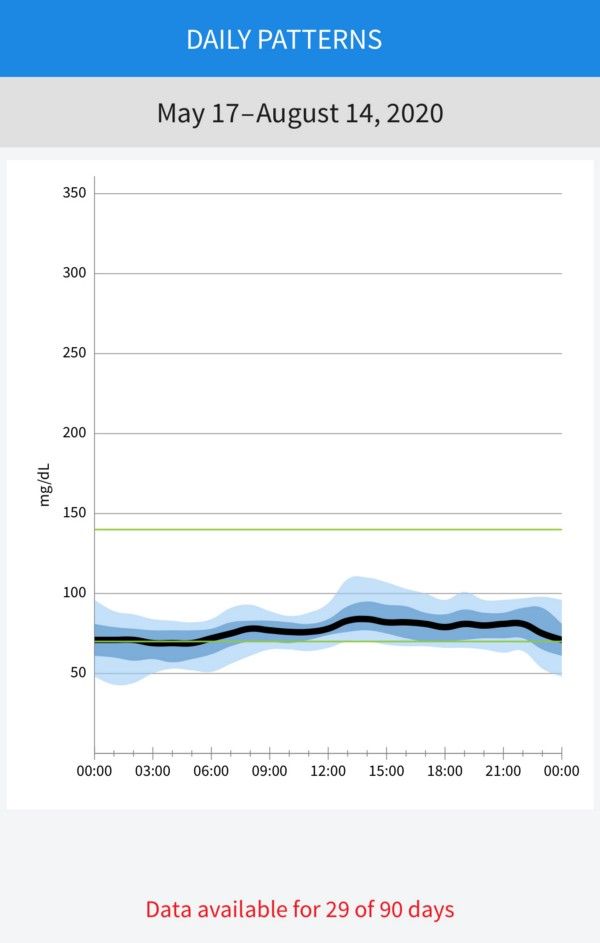

I did this probably from most of July through early August, and I also did a week of fast-mimicking diet with something called Prolon. I wanted to show you here my average glucose chart. And you can see on the last page this chart of where I averaged at over time.

Casey:

Really good.

Matt:

It’s good?

Casey:

Yeah, I would say it’s super good. I can give you an overview of what is normal and what’s optional.

Matt:

Yes, please!

Casey:

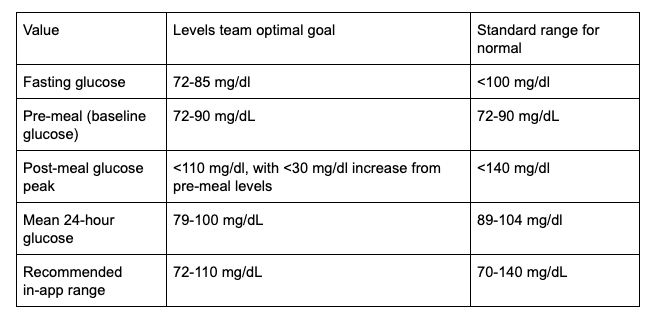

Right now, the only criteria someone has to know whether they’re normal or not normal in terms of their blood glucose is our standard criteria that the American Diabetes Association puts out there. It basically says that if your fasting glucose (your glucose first thing in the morning with no calories consumed for eight hours) is less than 100, then you’re considered “healthy.” 100 to 125 is pre-diabetic, and 126 or above is diabetic and then there’s two other ways to test this, which is your hemoglobin A1c, which is the blood test that shows your everyday average. 5.6 or below is normal, 5.7 to 6.4 is pre-diabetic, and 6.5 and above is diabetic.

These are just general buckets, but these categories don’t tell you whether you’re doing well, if you’re in the optimal range. Something that I spent a lot of time over the last year working on is trying to look through all of the literature, the scientific literature and say, “what are probably the ranges we should be shooting for?” Under 100 for a fasting glucose is pretty general, and people want more granularity into that. So from the research literature, it actually looks like we should probably be striving for more of a range of between 70 and 120 for pretty much all the time during the day and that our fasting glucose should probably be between 72 and 85, so not just right up at 100. If you look at healthy populations of individuals who are non-diabetic wearing CGMs, they will stay between blood glucose levels of 70 and 120 for 91% of the day.

In terms of average glucose, if you put CGMs on non-diabetic individuals, the average glucose tends to be between 102 and 105. Yours is 77, so you are way below what even healthy individual’s average 24-hour glucose is.

Matt:

Well, I think a lot of that is because I spend a third of my day sleeping and they get really, really low, down to 40s sometimes in the middle of the night. I don’t get woken up, and I’ve talked to my doctor about it but I think that’s skewing the average.

Casey:

Yeah. Even between 12 and 3:00 PM, you’re still only at an average of 86, which is good. In the research, it says that an average of 105 is considered a normal person.

Matt:

Got it.

Casey:

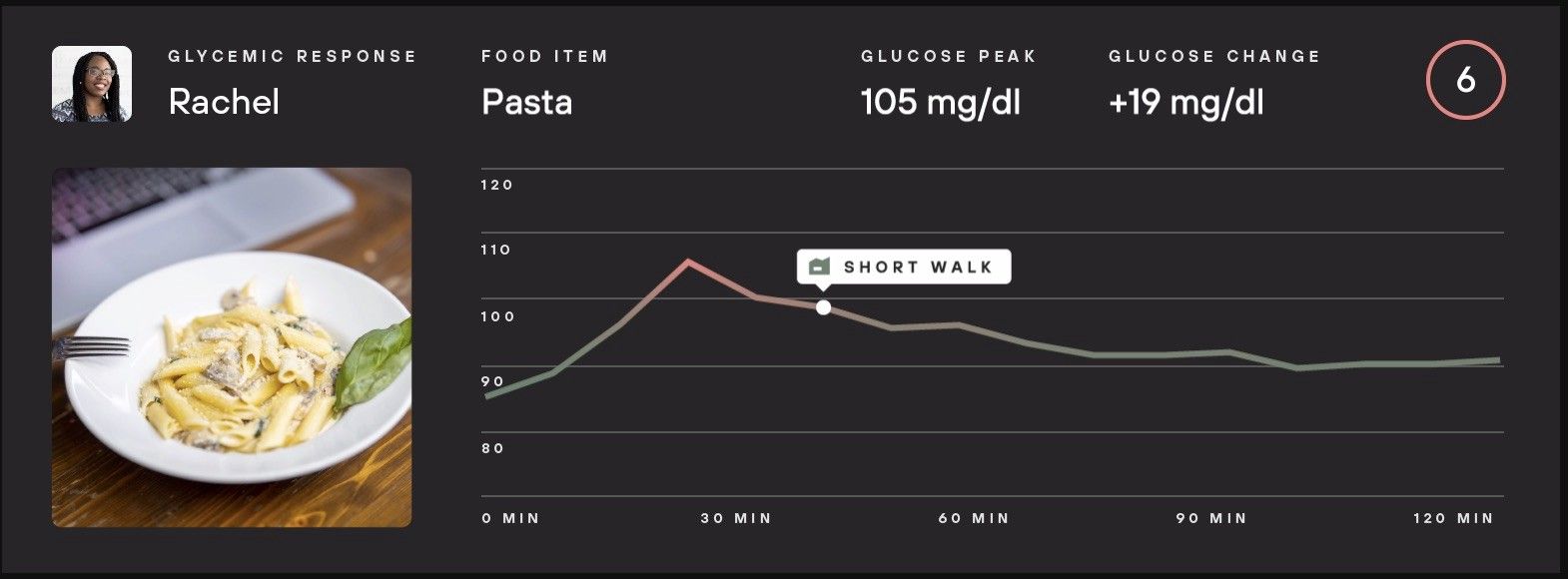

So yeah, that’s really good. Personally, I’m trying to not get it above a 15 point increase after a meal, trying to stay within 15mg/dL of your baseline. The reason that we recommend shooting for a fasting glucose between 70 to 85 as opposed to just below 100 is because there’s research that shows that as you move up within the fasting glucose range towards 100, you have a much higher chance of getting diabetes, having a future stroke, or having a future heart attack. Even though it’s considered the bucket of normal, it seems like people do a lot better when they keep their fasting glucose in the lower ranges of 70 to 85.

I firmly believe we need to have essentially a new research consensus now that CGMs are coming online and people are more aware of their glucose, [for] someone who wants to optimize their health, what glucose level that they’d be shooting for. That needs to be determined as a group in the medical community.

Matt:

Absolutely, yeah. I feel like I’m on my own. I’m feeling like I’m this weird biohacker, and I’m walking around with this thing on my arm and people are like, “Matt, are you diabetic?” That leads me to the next part of this conversation I want to explore, which is your beta with Levels and what prompted you guys to take some of the things that the FreeStyle Libre introduced and improve upon it, where you see this mainstream adoption of the market. How does this become normalized in society?Casey wears a FreeStyle Libre sensor covered with a custom Levels patch.

Casey:

I would say our target audience for our beta is going to be the early adopter types who are really looking for performance enhancement, longevity. This is the biohacker type like you said. What’s interesting though is that as we’ve run our beta, some interesting groups have emerged really organically as people who are buying for this type of technology and I would say that those groups section out into the weight loss community. Traditionally, there’s this model of weight loss as calories in, calories out, and we’re realizing more and more that that is the wrong model. We have to be thinking about hormones if we’re thinking about weight loss. If insulin is high, you’re not burning fat so if we’re not thinking about insulin, we’re not going to lose weight.

There’s a lot of really savvy people in the weight loss community who are aware of this and a lot of that’s due to the amazing work of people like Jason Fung, who wrote The Obesity Code, The Diabetes Code and people like Ben Bikman, who wrote Why We Get Sick, that really talk about this stuff. So they’re like, “I need a CGM and my doctor won’t prescribe me one because I’m not diabetic,” so they seek out a company like ours. The weight loss community is a big one, the biohacker community obviously, but then also the professional sports community. This has been a group that has been incredibly engaged with us. We’ve been in talks with over 13 professional sports leagues, because they’re really looking for a better understanding of how to fuel their performance and especially when you think about endurance, fundamentally, [which] is being able to work for longer with consistent energy.

To do that, you really do need to have this balance between burning glucose but also being able to burn fat. To be able to develop what we call “fat adapted” AKA being able to burn fat for fuel, you do need to start training in a low carbohydrate, low glucose state but it’s very hard to know if you’re in a low glucose state while you’re training. Having a CGM on can really help you move towards training in a way that’s going to let you flex those fat burning pathways, so that’s been a really interesting community that we’ve been working with a lot. There’s a number of others that we’ve seen. Women’s health I think is emerging as a really big one. The leading cause of infertility in the United States is polycystic ovarian syndrome which is essentially insulin resistance of the ovaries. It’s a metabolic disease, and diet has been shown to be really effective, low-glycemic, low carb diets for reversing this type of infertility, but again, it’s hard to make these consistent changes in diet and lifestyle if you’re not seeing the data history and if you don’t even know if you’re doing it right.

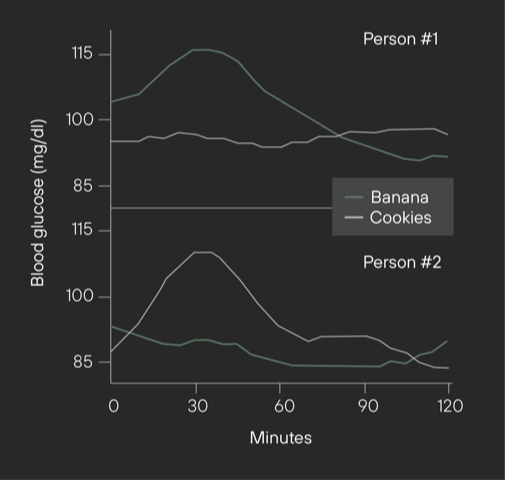

The fifth segment is the people who just are so interested in finding out what the right diet is for them. There’s just such tribalism in nutrition right now and it’s like warfare between the vegan, the keto, the paleo, and the carnivore. The reality is that there’s probably not one diet that works for everyone, there’s been some really super interesting research. This paper really was one of the origins of our company out of the Weizmann Institute in Israel, Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses.

The idea that two people can eat the exact same banana and have completely different glucose responses. That banana might be a good metabolic choice for one person and not a good metabolic choice for another person and what that group found was that microbiome was one of the key predictors of how people responded. There is no one size fits all diet. There are a lot of people who are really desperate to find the diet that works for them and this is the first tool ever that can close the loop on nutrition for people in terms of, you eat something and you know specifically whether it is a good or bad choice for you.

There hasn’t been anything other than a CGM [as] a tool for that. You can imagine you could get on your scale the next morning and see if you gained weight, but you wouldn’t be able to even link that to one thing the day before, or you could go into your doctor’s office in six months and get a glucose test. But again, you’re not connecting that with any one thing from your diet. So the beauty of CGM is the one-to-one relationship between specific foods and whether it’s good for you from a glucose perspective.

Matt:

So there’s all these factors that play a role in that. There’s exercise, sleep, diet. How does Levels become this kind of hub for all of these sensors that have become more popular, whether it’s the Oura sleep ring, the gut test, or logging food. How do you guys play a role in that, in the short-term and in the longer term?

Casey:

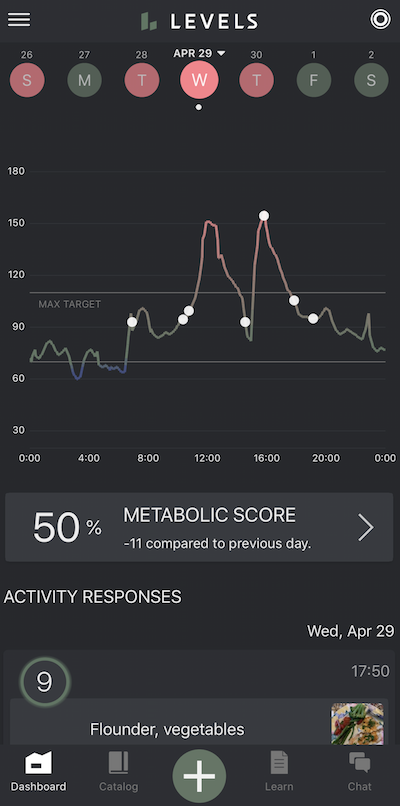

So the Levels program, fundamentally, is a behavior change program. Everything we’re doing in the app is to help guide people towards making smarter behaviors. All of our product features make it very obvious to people the relationship between what they did and what happened. From the standpoint of the app, that means a really engaging interface for logging food. We have a proprietary scoring system called a Zone Score, which takes a number of glucose metrics and converts them into a very simple score that people can use to understand the impact. The key thing here is that it’s not a meal score, it’s a Zone Score, and the reason for that is because like you said, there are a lot of things that lead into this glucose readout.

The main things behaviorally are sleep, stress response, exercise, and food. Let’s say you exercise 20 minutes after you ate a banana, and you also run a podcast and were stressed out. All of those things are going to lead to a glucose output, so you have to be able to actually tell people what were the factors that led to a glucose response. You have to have all that data, so we take those different pieces of information, put them into a Zone Score and then over time, as you log lots of different behaviors and activities, you can start to use this higher level machine learning to parse out for people like: “it looks like when you have stressful events, this impacts your glucose in this way. It looks like when you take a 20-minute walk within an hour after meals, you have a 30% less glucose rise.”

You start building metabolic awareness and what we call a “metabolic toolbox” so that you know what to pair together and what to work on to really get that flat glucose line. For some people, it’s going to be mostly stress. Sleep is so huge, getting five hours of sleep or seven hours of sleep could completely shoot you in the foot, so we can start telling people that. We take in Google Fit and Apple HealthKit data. Within those data streams, we can start to see things about activity, sleep, and heart rate variability, which is an objective measure of stress. People are logging their food directly in the app, and then these things are essentially parsed out to tell people very simply what’s working for them and what’s not.

Matt:

So the passive piece is like the Apple Health data from the data scope or the Apple Watch?

Casey:

Mm-hmm.

Matt:

Could they log a mood to say that they’re stressed?

Casey:

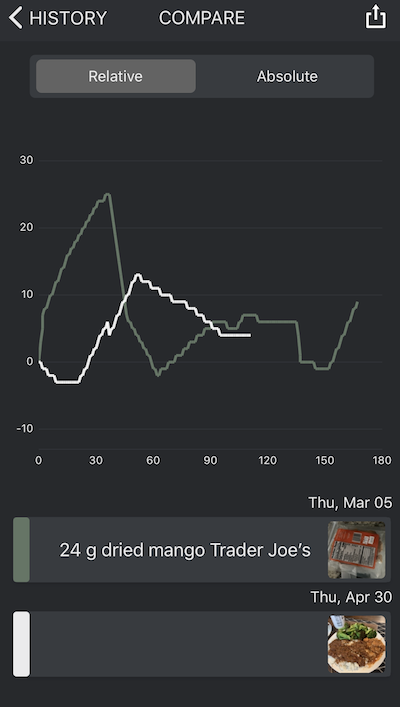

Yeah, you can log a mood, you can log exercise, you can log any food [and] any other notes that you want actually. The nice thing is that those all go into what’s called an activity catalog, which is essentially the organized list of everything that’s been going on and you can start to compare different zones. So let’s say you did oatmeal plus peanut butter plus walk. That’s one zone, and you got a score of nine and then, you did oatmeal plus just peanut butter and you got an eight. You did oatmeal plus walk and you got a seven. You can actually graph all of those and compare your responses to all of them, and just start seeing the variables that are helping. As our population of data gets bigger, we can start to then move more into the predictive responses.

So if you were to have a similar gluco-type to a different person, can we potentially start predicting how you’re going to respond to a different type of food? A lot of that research is coming out of both the Weizmann Institute, but also Michael Snyder at Stanford who’s doing work on gluco-types, different types of responses to glucose. There’s a lot you can do with the population piece as well so we’re expanding our engineers weekly and getting all these features built. Right now, we’re seeing amazing improvements on a lot of our early beta customers. We’ve had about 800 people go through our beta program. We have 26,000 people on our waitlist and we’re just trying to get to the best product possible to market super quickly.

Matt:

I’ve seen the @glucosegoddess. She does a really great job on her Instagram showing “I ate two slices of pizza without a salad. Here’s what happened. The next day, I did the same thing but I added a salad and here’s what happened. Hey guys, did you know that if you add fiber or try doing this, it might work.” But it doesn’t work for everybody, right?

Casey:

Right.

Matt:

And that’s what it comes down to. I’m shooting a HNGRY episode about the personalized nutrition market where I have people wearing glucose monitors, and they’re testing Apple cider vinegar shots while they’re eating certain food, adding milk to oatmeal, drinking coffee with and without ghee (butter), or eating sourdough bread vs. store-bought bread.

Casey:

Amazing, yeah, I think the microbiome piece is [exciting]. Right now, that’s not a part of our core offering, but that is certainly related. [There’s] a lot of research on Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and these different bugs. [If] they’re in the wrong ratios [you] are much more likely to have metabolic disease or obesity, so those mechanisms are becoming more and more clear and it’s pretty interesting.

Matt:

So can we dive into that for a second? I’ve done three of these tests already: Viome, DayTwo, and a Sun Genomics probiotics test. They all do the same stool sample testing. Let’s just say there’s an API layer that’s similar to Apple Health where we could grant a level of access to that data, assuming there’s enough of a population. What inferences would you be able to make for me that you wouldn’t be able to do today with that kind of data? What would that unlock?

Casey:

Yeah, well with what DayTwo is doing, they’re actually taking the stool data and giving you a list of what foods you’re likely going to have a good response to. They’re making predictions, but if you actually added the real hard data layer, it would be able to actually optimize the model. So that’s pretty cool, I don’t think they’re doing that at this point as far as I can tell.

Matt:

They don’t have access to my FreestyleLibre data.

Casey:

Right, so that’s the connection that it would be very cool to have [and] refine the predictive model that they developed in that paper. I think the broad brush strokes are that obesity is associated with an increased ratio of Firmicutes bacteria to Bacteroides. You want to get these ratios cleaned up and you can do that by improving essentially what you feed the bacteria. You want to do everything you can to basically support your microbiome; from my standpoint, that’s going to be lots of fiber. The average American eats 12 grams of fiber a day. We should probably be eating 50 to 75 grams of fiber a day. It’s like literally 5X. The second thing would be, avoiding pesticides, unnecessary antibiotics, or antibiotic exposure where it’s insane in this country and then eating a really low to reasonable amount of animal protein.

We eat so much animal protein in our diet, and that can lead to metabolic byproducts from the microbiome like TMAO and these things are not good. Antibiotics, pesticides, low fiber, too much meat — we’re just really not very kind to our microbiome. Another thing that’s really important to remember is that chronic stress really is detrimental to our microbiome. A huge percentage of our nervous system is in our gut, the enteric nervous system. The microbiome in our gut feels all the psychological stress that we’re feeling and then ultimately, the microbiome produces short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which are metabolic-optimizing chemicals. They’re producing byproducts that help us do our metabolism better.

Right now, that’s not something that’s really a big part of the Level’s product because it’s not an immediate behavior change cycle that we’re really focused on but it’s something certainly that I think should be more known about and we should be eating a lot more fiber.

Matt:

I guess to close out, going back to what we were talking about with the healthcare system and our food system, I think I read on your blog that over a third of our population is either pre-diabetic or diabetic.

Casey:

Yes.

Matt:

You’re very much a first principles thinker. What are the things that we need to do to create a healthier society and align incentives within those two systems?

Casey:

So first of all, I would say the lowest hanging fruit we have to improve healthcare spending and the overall human capital and health of our country is to approach metabolic dysfunction, bar none. It is actually a beautiful thing to intervene on because 88% of Americans are metabolically unhealthy. It’s tied into every major chronic disease we face right now and most chronic symptoms, and it’s readily reversible rapidly with essentially free interventions around diet and lifestyle. If doctors aren’t thinking about how to improve metabolic health in their patients, they are not doing their job properly. End of story.

I think the first thing that it’s going to take is education. This needs to get in the zeitgeists of common lexicon that people are talking about with health, and that’s happening. I think sometimes it does take the early adopters to move in that direction before it’s on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Then ultimately, I think a lot of it is going to come down to showing costs, that this is a high value intervention to approach metabolic health with behavioral change tools like Levels. Unfortunately, a lot of the system and the incentives are run by economics and showing that this is going to be cost savings to payers and hospital systems is going to be a big part of that. From a food industry standpoint, I think that as people understand their relationship to food better, how food is actually affecting their health, and their day-to-day performance, it will drive consumer demand to be different.

I think that when people know what is hurting them and causing the problems in their life and [start] closing that loop, they will start making different consumer decisions [which] will move the food industry forward. I don’t have a lot of faith that the food industry is going to change on its own. I think that it’s going to change because people understand things better and push. We’ve seen this in the organic food movement, we’ve seen this in the vegan food movement. Consumers ask for things and companies will follow. I think we’re going to see a massive shift of companies having to respond to people saying, “This is crazy what this is doing to my blood sugar. I want a different option.”

On a more systems level, I would say there’s a really great article that was written by Bill Frist, the former Senate majority leader in CNN last week that was called, “The US food system is killing Americans” that really outlines a lot of the key factors at play. One factor that needs to change is our farm bill spending. Right now, we spend hundreds of millions of dollars subsidizing crops that cause disease in Americans, things like corn, soy, wheat. That needs to change.

The amount of subsidies that actually goes towards fruit and vegetables and beans, which are actually called specialty crops, as if there’s something special (they are just crops), is like a fraction of what goes towards commodity crops which are the disease-promoting foods. The public funds that we use to subsidize food for low income individuals like SNAP and WIC basically allow people to buy whatever food they want, and a lot of that food spending is going towards processed, disease causing food. Healthcare-wise, moving towards more of a value-based care system that promotes prevention but in the meantime, helping people realize what’s actually going on in their bodies I think is a first step to drive a lot of these things, to drive both food decisions and voting decisions.

Matt:

Awesome. Well, this has been really, really cool to chat with you about all this stuff. I think you’re doing amazing work. So thank you.

Casey:

Yeah, thank you.