Read Time

6 min

The big news this week is that Wonder is buying delivery marketplace Grubhub from Just Eat Takeaway for $650mm, $500mm of which is assumed senior debt, after it was acquired by the group for over $7bn in stock in 2020. The 90% discount is a reflection of the Dutch multi-national’s failed attempt to create the largest food delivery business in the world excluding China, that began with the merger of Takeaway and Just Eat that same year. Fast forward to Wonder, which calls itself “a new kind of food hall” and has built a portfolio of acquired and in-house businesses including: $60mm+ of restaurant IP, Blue Apron meal kits, Relay last-mile logistics, and nearly 30 multi-brand restaurant locations. Beyond building an aspiring public holding company for flailing foodtech businesses, it remains unclear what strategic value, if any, of these semi-related businesses could unlock– a topic for a future post. But the $1.1bn of total capital raised for Wonder’s “IAC-inspired” portfolio begs the question– what is the significance of the modern food hall and the tech that powers it?

Note: today's HNGRY Trends is brought to you by NextGen Kitchens. Interested in paid editorial? Email info@hngry.tv

The future of food halls

Taking a step back, it is becoming more widely accepted that when it comes to the future of delivery, the pure-play ghost kitchen model has yet to work for anyone besides QSRs with outsized delivery demand that negatively impacts their in-store experience (e.g. Starbucks). CloudKitchens has diversified its business model by doubling down on its software division, Otter, and build-to-suit development for QSR brands under its ProFoods subsidiary. Similarly, traditional food halls with multiple tenants and kitchens under a single roof are under pressure amidst rising labor and food costs as well as a shift towards digital demand. Unless they are located in highly trafficked areas immune to work-from-home trends and equipped with proper delivery/pickup infrastructure (egress/ingress, lockers, etc), such landlords/operators will find it increasingly difficult to justify their above-average per square foot rents.

However, what has seemed to catch on is the “airport food hall” model of startups like Local Kitchens, which recently raised a $40mm Series B, that prepare a handful of brands out of a single kitchen for dine-in, pickup, and delivery. There are nuances to this approach with regards to Local Kitchens’ scratch cooking vs. Wonder’s TurboChef model as well as the structure of its licensing deals. Whereas Local Kitchens licenses concepts from known chefs and operators, Wonder has spent over $60mm acquiring exclusive rights to its chef-backed restaurant concepts. Lastly, Local Kitchens renovates second-generation restaurant spaces for its locations while Wonder’s commissary-driven ventless approach allows it more flexibility with the types of leases it can sign, including locations located inside of Walmart, founder Marc Lore’s former employer.

Complexities of multi-brand operations

The challenges of these models were recently highlighted in a HNGRY article about Byte Kitchen’s pivot away from the omnichannel food hall model towards software. In summary, these were largely issues surrounding the operational complexity of cooking multiple brands on a single line, technology powering multiple brands in multiple locations, and the resulting unit economics that didn’t prove to outperform a single-concept restaurant thanks to third-party commissions, licensing fees, and intricate procurement logistics. Perhaps Wonder’s Grubhub acquisition solves the customer acquisition problem and its recent sale of its commissaries to Blue Apron manufacturer FreshRealm solves the food problem. But for any operator who isn’t VC-backed, what about the technology problem?

Given all of these learnings, it seems that the best path forward for multi-brand food and beverage businesses is a single-operator, multi-concept model whose sales aren’t entirely reliant on marketplace rankings, but rather a compelling tech-enabled dining experience. A great example of this is Aster Hall, a six-year-old 22k sqft food hall from esteemed hospitality group Hogsalt, located inside of a Chicago mall that I visited last weekend. All brands are owned-and-operated by the group, which owns concepts like Au Cheval and Sawada Coffee, which can be mixed and matched via kiosk, mobile QR ordering, or on DoorDash. Its two floors of food “vaults” (concept-designated pickup stations), cozy booths, co-working area, lounge, and bar satisfy the goal of full daypart utilization. In fact, the hall’s tagline reads “where coffee meetings turn into happy hour.”

Aster Hall in Chicago blends 22k sqft of bar, lounge, and dining area with a shared kitchen powering a handful of O&O Hogsalt fast casual brands (Source: HNGRY)

Where offline meets online

When it comes to executing the technology, there have been few vendors to streamline both in-person kiosk and QR ordering as well as off-premise delivery/pickup sales for food hall-style operators. Enter NextGen Kitchens, a new Vancouver-based startup founded by restaurant operator-turned tech entrepreneur Ash Nabavi. After founding his own local commerce startup, Nabavi decided to immerse himself in the foodservice space by franchising a Canadian salad concept five years ago, uncovering the headaches of piecing together disparate data sources to get a real-time snapshot into how his business was performing. During the pandemic, his experience of adding virtual brands amidst shuttered dining rooms eventually led to him remodeling his restaurant into a multi-tenant digital food hall. This became the genesis for NextGen Kitchens as the brains to power his entire operations.

“Nobody has paid attention to this market in a way to understand all the things that are important to operate,” said Nabavi in an interview with HNGRY. “My north star is that I lived that experience of an operator. I know how hard it is to manage a food hall. I built these tools so that if I were the operator myself I would make the best out of them so I can run an amazing business.”

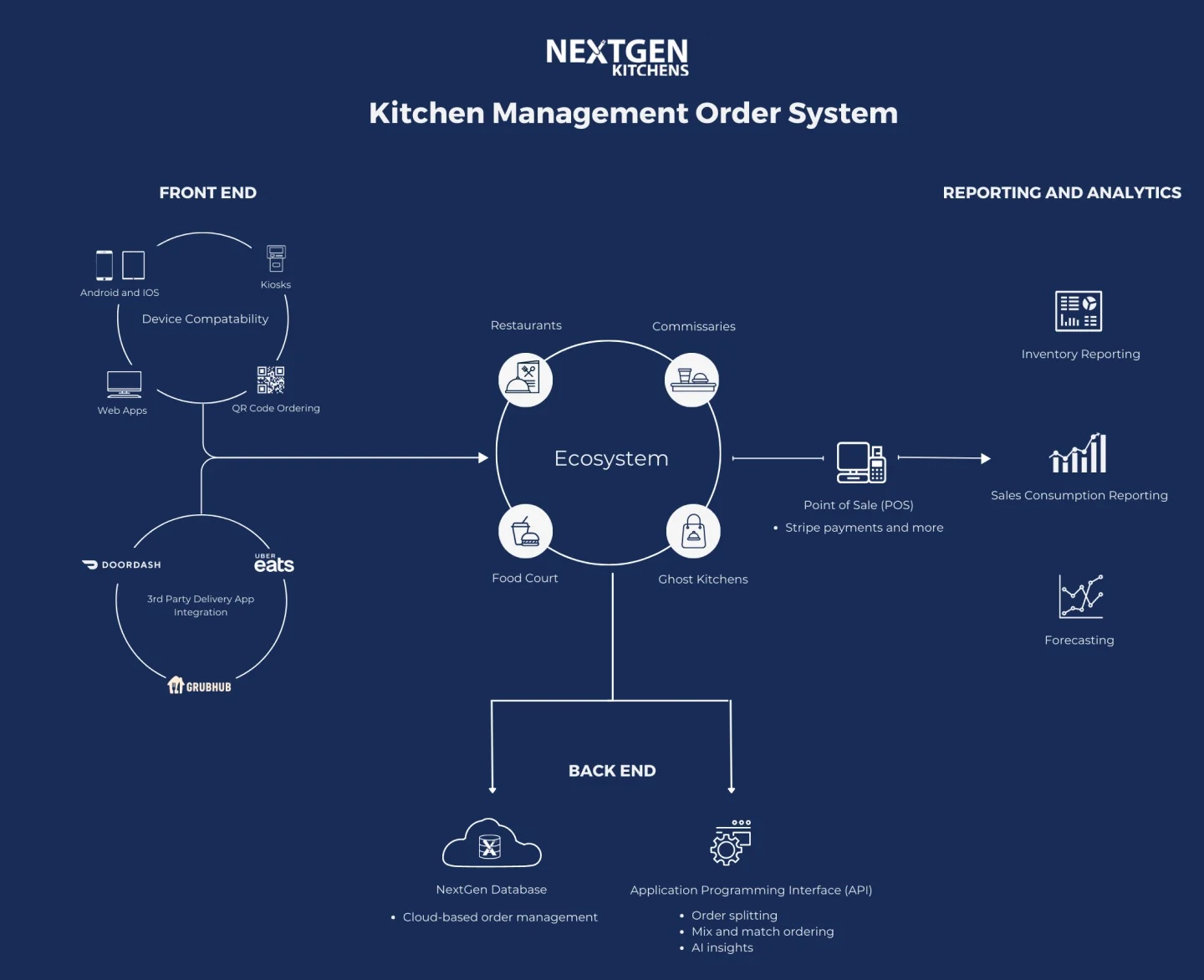

NextGen’s suite of tools includes kiosk and QR ordering, native mobile and web-based ordering, payment and order splitting, and consolidated reporting. What this ultimately means is that in the front-of-house, consumers can order across multiple brands in a single ticket and in the back-of-house, licensees or operators of those brands can quickly receive disbursements without a manual accounting process. Furthermore, tickets can be split across multiple kitchens or stations to fulfill a multi-brand order as frictionlessly as possible.

Beyond food halls, Nabavi sees NextGen also powering multi-brand franchisors that want to create a consolidated consumer-facing marketplace of their various brands. The startup recently hired 30-year hospitality vet Neil Thompson, as Chief Strategy Officer to head its business development efforts. Thompson most recently was the VP of Digital at HMSHost, the master concessionaire behind franchised food and beverage concepts at many airports. Prior to that, he held leadership roles at Nando’s and Tim Hortons. In a recent podcast interview with HNGRY, Thompson said that digital ordering at airports now accounted for ~25% of all sales.

In Conclusion…

If Wonder’s poaching of Amazon’s former SVP of Worldwide Grocery Stores is any indication, there is immense value in combining experiential retail with technology. While the pandemic shifted the pendulum far towards the delivery-only ghost kitchen model, a new equilibrium is shaking out that leverages the best of both offline and online channels. Next month, Goop Kitchen parent DFG Ventures will launch a new curated food hall in a former restaurant space that will feature grab-and-go and fresh-prepared meals from brick-and-mortar concepts like Mini Kabob, The Cheese Store of Beverly Hills, and Joan’s On Third as well as influencer-powered ones with What's Gaby Cooking. While Amazon and Wonder have plenty of Monopoly money to test their brick-and-mortar formats, food entrepreneurs do not.

Hopefully we’ll see more technology players emerge to let operators focus on what they do best: build ‘third places’ and provide the requisite hospitality we so desperately crave.