Read Time

6 min

All photography courtesy of Zuul

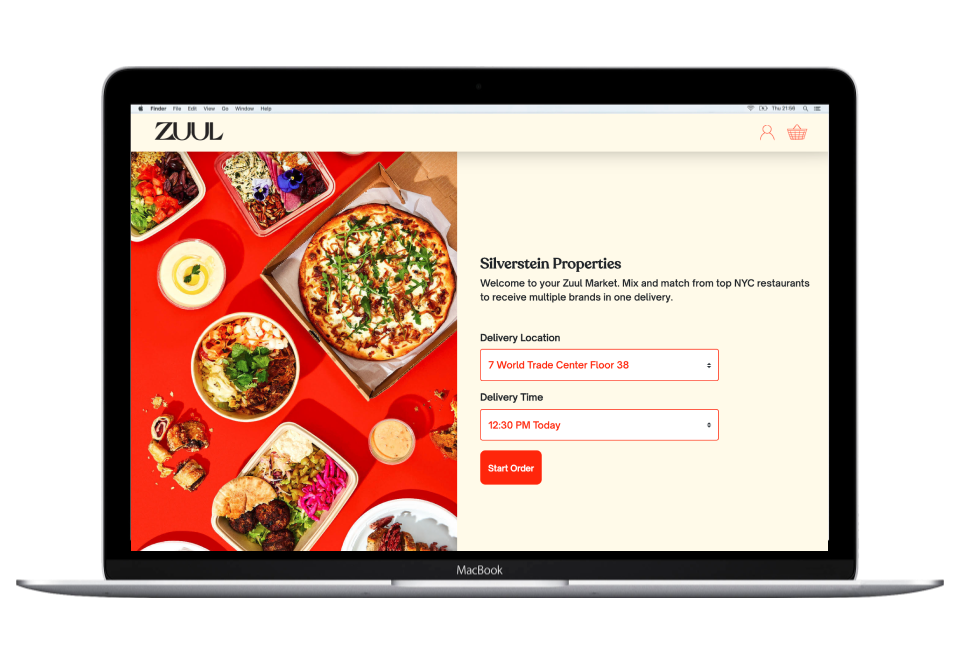

“Delivery as it exists today is a $26bn market that everyone hates,” says Corey Manicone, co-founder and CEO of Zuul Kitchens, NYC’s first ghost kitchen operator. “It’s one person delivering food from one restaurant to one location. It’s tough to find a winner in that equation.” Zuul is optimizing that by delivering multiple orders from multiple restaurants to one location using a single courier. “Having multiple brands under one roof allows us to change the game,” he adds.

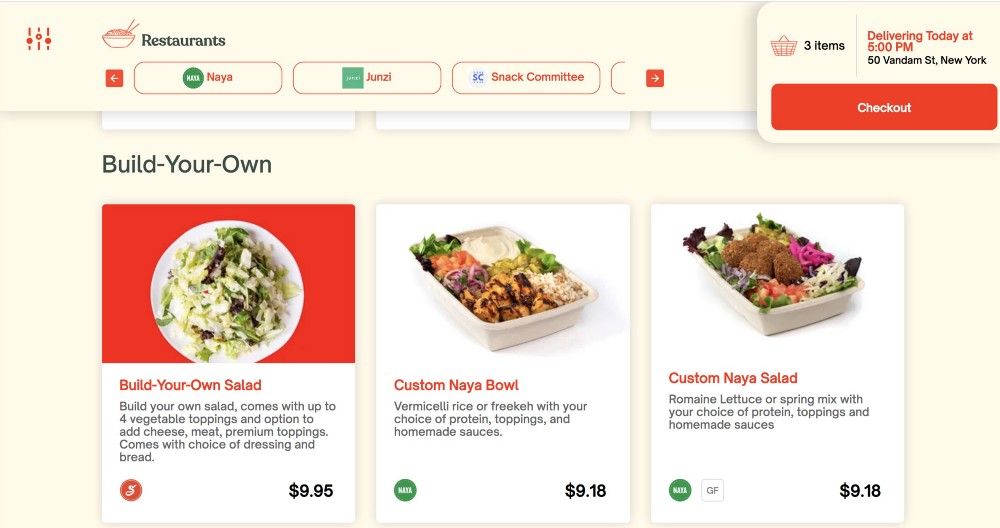

The startup has been heads down on solving the challenge of boosting average order values for its local restaurant tenants Stone Bridge Pizza, Naya, Junzi, and Sarge’s Deli. Last year, it launched its first 5,000 sqft facility in the heart of Soho with five restaurants and a meal kit operator. Over the last six months, it has been beta testing its own multi-concept direct ordering and delivery platform that has partnered with local office and residential buildings in Manhattan to batch delivery orders on a limited schedule, drastically reducing the cost of its deliveries. An average delivery within Zuul’s core downtown NYC radius costs about $5, but can now be split across up to as many as seven orders, bringing the average delivery cost per order to less than a dollar. These fees are either subsidized by landlords or passed down to the consumer.

The service is similar to what Sweetgreen had created with its Outpost strategy, waiving delivery fees for members of WeWork and other partner office spaces that had preset delivery times for pre-orders. But instead of just getting Sweetgreen delivered for free, employees in office buildings like Silverstein’s 4 World Trade Center or residents in buildings owned by Broad Street Development can order from custom portals that aggregate menus from six different physical and virtual restaurant brands as well as Snack Committee, a Zuul-branded virtual bodega largely comprised of New York CPG brands. The product is currently being marketed to landlords and office managers as Zuul Market, “a virtual food hall powered by ghost kitchens.” Altogether, the consolidated menu curates over 100 dishes at any given time that can rotate based on the time of day or based on a landlord’s choosing. Zuul operates a two-step aggregation process where it collects all the orders across various restaurant tenants and then bags multiple orders into a single tote that gets unpacked and distributed within a building at the point of delivery. All portals are hosted under yourbrand.zuul.menu.

“It’s not a new amenity, it’s a new way of doing delivery,” says Manicone. “We’re leaning into our mission of helping people thrive in the business of food.”

The platform was born out of Zuul’s acquisition of Philadelphia-based Ontray Technologies in late 2019. To fulfill orders placed through its market, Zuul has integrated with local fulfillment services NPD Logistics and Relay. Manicone was an early employee at Relay, which uses bike couriers to handle first-party delivery for restaurants in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. NPD is a white-glove provider that’s insured to provide deliveries to Class A residential buildings and uses UV-C light to sanitize packages delivered across the tri-state region.

While larger operators like Kitchen United and CloudKitchens have attempted similar strategies to boost average order values by allowing consumers to order across an array of concepts, they fall short of offering a sustainable model for restaurants. Despite building a fully white-label solution for its tenants in LA, Chicago, Scottsdale, and Austin, Kitchen United’s Mix platform has yet to leverage its relationship with investor RXR Realty, which owns and manages 93 commercial, residential, and retail spaces. CloudKitchens, which teased its “Internet Food Court” concept in April, quickly removed its physical and digital presences after HNGRY had published a scoop that was picked up by the Financial Times. Even still, CloudKitchens has yet to launch its own direct delivery platform, instead opting for “superstores” like its West & Mel Food Co listing on delivery marketplaces that charge standard commissions bemoaned by its tenants. If you were ever wondering how to order Pampers, Sweet Rose ice cream, and Kreation Organic in a single Postmates order, look no further than to Travis Kalanick.

As many brick-and-mortar restaurants witness delivery account for over 60% of their sales amidst the pandemic, the economics of selling on marketplaces becomes nearly impossible to turn a profit with existing labor, rent, and food expenses. According to former by Chloe CEO Patrick Hellstrand, a restaurant that did $1mm in sales pre-Covid that spends 25% on rent, 30% on labor, and 30% on food would lose $200,000 if ⅔ of its existing customers ordered via delivery. To break even in that scenario, the restaurant would need to double its delivery sales.

Zuul says it has never had any relationship with the third-party delivery marketplaces its tenants use. Manicone is more worried about keeping his restaurants thriving in an off-premise world than he is about closing any doors with the big three marketplaces as he pushes direct channels.

“There is a world where 100% of their business comes from Zuul Market. It’s the best margin business for our brands,” he says. “I think we’re going to make decisions that are best for the members, that’s what’s going to set us apart from others.”

Meanwhile, many players large and small are jumping on the direct ordering bandwagon. For example, a team of entrepreneurial students at Duke University launched GoBringIt, an ordering platform powering deliveries for nine virtual brands and physical restaurants around Durham, NC. Partners include Unilever, T.G.I. Fridays, and a handful of mom and pops to select drop-off points. Reef Technology has recently begun testing its own direct-to-consumer virtual convenience store from two managed parking lots in Miami called Stock-Up-Mart with Unilever and Procter & Gamble. It too waives delivery fees for local orders placed directly on its website.

For Zuul, its software platform could allow it to scale into new markets much faster than other ghost kitchen operators by allowing existing landlords, like food halls with a concentrated supply of restaurants, to unlock a community-based virtual food hall in a matter of weeks. For example, New York-based Urbanspace has partnered with Ritual to offer online pickup and delivery for some of its stalls in its Midtown food halls, but it’s a 1:1 system that lacks the flexibility of ordering across any of its restaurants. With Zuul Market, Urbanspace could tap into demand from nearby residential buildings to offer free delivery if consumers pre-ordered a few times a day.

“The core of Zuul Market is connecting supply to demand. Right now our Zuul Market supports our infrastructure however we can layer that exact technology on other multi-concept infrastructure: mall food courts, universities, food halls etc. We’re exploring a handful of opportunities that may not be Zuul’s infrastructure but helps us lean into our mission.”

If we want to create a sustainable model for delivery, we may have to accept that when it comes to price, convenience, and selection we can have anything but not everything. If that means ordering from a portal that offers a small handful of delivery windows per day, then so be it.

Before I forget… “hey Siri, set a reminder to order my corned beef sandwich, Wandering Bear cold brew, and a margherita pizza for 10:30 AM. Thanks!”